26 May, 2012 HONIARA - It is early morning when representatives from UNDP, CTA, TNC, and from NGOs from PNG and the Caribbean region travel to Naro village to transport the 3D model and officially hand it over to the community. Ms Winifred Pitamama, from Boeboe village, is among the group.

Squeezed between the blue sea and the lush hillside forest, the coastal road winds across coconut plantations, patches of grassland and some secondary forest. The road crosses river beds and offers astonishing views of marches and mangroves.

From time to time it sides small villages where stilt houses are prevalent and makeshift markets where - under the shade of huge trees - women sell fruits and vegetables and occasionally grilled fish and rice wrapped in banana leaves.

When the delegation arrives in Naro the sun is already high in the sky. The P3D model is unloaded from the pickup and displayed in a shaded area at the centre of the village.

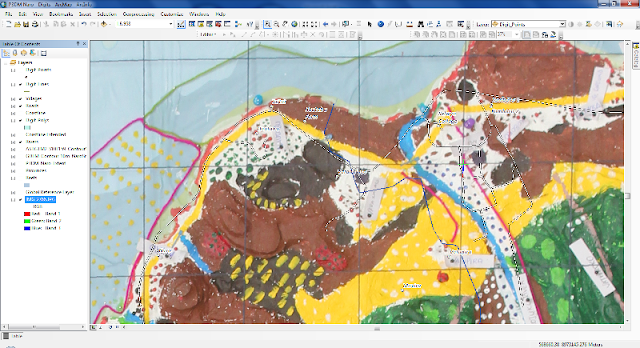

The first to come are Naro’s representatives that worked on the 3D model during the workshop in Honiara. Then, gradually, other men come forward, followed by children and finally by women. Two elderly ladies join the group. Once a small crowd has gathered around the model, Jacob Zikuli, AF-SWoCK Project Manager, introduces the objectives of the visit to community members. He recalls the work carried out during the week by the students in manufacturing the blank model and by Naro villagers in developing the map legend and consequently in populating the model using colour-coded pushpins, yarns and paint. He shared his perception on the efficacy of the participatory 3D modelling (P3DM) process to collectively plan the management of natural resources and to strategise on climate change adaptation.

Thereafter Jacob invites Joseph Salima to describe the legend items displayed on the model on behalf of Naro representatives that participated in the work. Joseph provides a detailed explanation of the areas, line and point features. He refers to the legend to indicate the codes used and names all features in vernacular and English language, while pin-pointing to them on the model.

After his presentation, Ms Winifred Pitamama is invited to share her experience in manufacturing a P3D model in Boeboe, Choiseul Province, Solomon Islands. She took part in such an exercise in February 2011.

Winifred reports about the participation of women and children, the lessons learned by working on the P3D model and on how the community is making use of it at present. According to Winifred the model served to foster people’s awareness about their landscape, to identify mining areas within the territory and to provide evidence of the impacts of Climate Change on their lands. As the consciousness about these issues increased, villagers were able to collectively reflect on the long-terms effects of mining and on the potential impacts of Climate Change, such as those related to the raising of the sea level along the coasts, and take informed decisions to deal with them. Furthermore, as a teacher, Winifred underlines the value of the P3DM as an educational tool to be used in the school. Thanks to the model children were able to learn new facts about their territory, recognizing contour lines and landscapes. The model also contributed to raise awareness on Climate Change and environmental issues among the youngest generations. When Winifred concludes her speech, villagers seem to be more comfortable with the model displayed in front of them. Indeed, peer-to-peer sharing is always a powerful way to ensure good communication and learning among people.

The initial reluctance of the villagers gradually gives place to curiosity. Men, women and children start getting closer to the model and touching it. Through the physical act of touching, people could internalise the landscape more easily, and perceive themselves as the owners of the model. One elderly lady, who lived in the uplands, starts questioning the position of some feature-points, providing further information about the presence of additional landmarks up in the mountains that younger villagers did not know. From this moment, the community takes control over the model: adults call the children around the map to show the position of rivers, tracks, logging areas and protected areas.

The model offers the reference base for adults to transfer their spatial knowledge to young people, fostering the inter-generational transmission of local knowledge. It is a very exciting moment, that makes delegates fully understand one of the statements made by Giacomo Rambaldi at the opening of the workshop, namely that “participatory mapping is more than making a map”.

Indeed, participatory 3D models can be important tools to raise people’s awareness about their land, to identify the gradual impacts of climate change on traditional territories and to help to envisage possible future scenarios and take informed decisions. However, the “human side” of mapping is not less important. P3D Modelling can in fact be a way to bond community’s relationship, to elicit tacit spatial knowledge, making people aware of the fact that they know and that their knowledge is valuable, to strengthen inter-generational transmission of local knowledge and to revitalise vernacular language.

Now, it is time for the community to take the lead and to decide how to best make use of the model to serve their purposes. After agreeing on follow-up activities, the delegation leaves Naro village. Driving back to Honiara city, everyone feels happy. From today, Naro’s people have a new channel to make their voice heard.

Credits for the Honiara blogposts:

Authors: Giulia Pedone and Giacomo Rambaldi

Pictures by Giacomo Rambaldi

Location of Naro village:

Read more:

Squeezed between the blue sea and the lush hillside forest, the coastal road winds across coconut plantations, patches of grassland and some secondary forest. The road crosses river beds and offers astonishing views of marches and mangroves.

When the delegation arrives in Naro the sun is already high in the sky. The P3D model is unloaded from the pickup and displayed in a shaded area at the centre of the village.

After his presentation, Ms Winifred Pitamama is invited to share her experience in manufacturing a P3D model in Boeboe, Choiseul Province, Solomon Islands. She took part in such an exercise in February 2011.

Indeed, participatory 3D models can be important tools to raise people’s awareness about their land, to identify the gradual impacts of climate change on traditional territories and to help to envisage possible future scenarios and take informed decisions. However, the “human side” of mapping is not less important. P3D Modelling can in fact be a way to bond community’s relationship, to elicit tacit spatial knowledge, making people aware of the fact that they know and that their knowledge is valuable, to strengthen inter-generational transmission of local knowledge and to revitalise vernacular language.

Credits for the Honiara blogposts:

Authors: Giulia Pedone and Giacomo Rambaldi

Pictures by Giacomo Rambaldi

Location of Naro village:

View P3DM Where ? in a larger map

An initiative supported by:

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)