Joint press-release by CALG (Coalition against Land Grabbing) and NATRIPAL (United Tribes of Palawan)

Recent years have seen an exponential increase in land deals across the Philippines with the conversion of large expanses of land with crops mainly intended for export while traditional upland farming implemented through swidden (‘slash-and-burn’) technology (kaingin) is demonized and antagonized through restrictive legislation. The latter, however, fosters local self-sufficiency and plays a fundamental role in the livelihood and worldviews of indigenous societies.

Palawan, known as the “Philippine last Frontier”, in spite of its unique recognition as a UNESCO Man & Biosphere Reserve, has not been spared from massive investments in extractive resources and industrial agriculture, especially oil palm and rubber development. And yet, indigenous people and upland dwellers continue to be blamed for massive deforestation and ecological disaster. Not surprisingly, the recent front cover of a well known Philippine Newspaper (the Daily Inquirer, May 9 issue) holds a headline post with a powerful image that easily conflates all upland peoples as criminal agriculturalists “Images are powerful and can be damaging” says Wolfram Dressler a Research Fellow from the University of Melbourne (Australia) who has carried out extensive anthropological research in Palawan. ”They can direct blame without nuance and context. The masses (and government) absorb such images to reinforce centuries old narratives demonizing kaingin - a term that many farmers avoid because of its pejorative nature” adds Dressler.

The Inquirer’s article was triggered by an aerial survey carried out by the Center for Sustainability (CS), a nonprofit organization claiming to work for sustainable development in Palawan. The group spotted from the air key locations, previously covered by forest, and which have now been subject to clearing due to various external forces (mining, oil palm plantations and shifting agriculture (locally known as kaingin, or more appropriately ‘uma’). According to the group, in addition to clearing by ‘poor farmers’, forest burning in the south has been linked to the proliferation of palm oil and rubber plantations, and the main target of ‘slash-and-burn’ activities is the clearing of primary forests for development.

Ironically, for carrying out its photo survey CS conservationists alegedly borrowed the private plane of Jose Alvarez, the present Governor of Palawan, a well-known supporter of large-scale agro-industry, especially rubber which accelerates deforestation and deprives more traditional indigenous communities of their resource-base. He is chairing the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD). In principle, this government body is mandated to ensure the sustainable development of the whole province, through the implementation of the Strategic Environmental Plan – SEP (R.A. Republic Act 7611). The latter mandates that no development project should take place in Palawan unless the proponents secure the so called SEP clearance. Surprisingly, as of now, massive oil palm expansion and related forest clearing have taken placed unabated without SEP clearances. “Here in Palawan” says Marivic Bero (Secretary General of the Coalition against Land Grabbing - CALG). “We have the best laws in place to protect both the environment and the rights of our indigenous peoples. However, the limits of law lay within the implementation process, wherein rules and regulations are conditioned by the inability of concerned government agencies and their officials to stand by their own mandates”. She further argues that the government prohibition to ban kaingin represents a blatant violation of the major tenets of the ‘Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997’ (Republic Act no. 8371) which recognizes, protects and promotes the rights of indigenous cultural communalities. “This is a very powerful law” says Bero “and should not be undermined by ‘minor’ laws and municipal ordinances banning shifting cultivation (kaingin)”.

While Palawan environment is being affected by agribusiness (mainly oil palm and rubber), mining enterprises - and various forms of land grabbing - state agencies such as PCSD (as well as some Palawan NGOs) still view indigenous kaingin as ‘illegitimate agriculture’ and as the primary cause of deforestation. “Turning a blind eye to the plunder of forests by industrial logging, mining activities, agribusiness, and livestock production, state agencies continue to label and classify kaingin farmers as primitive, backward and unproductive who waste valuable forest resources, particularly timber” says Dressler. “In this way”, he adds “Government agencies have unleashed anti-kaingin campaigns that justified the resettling of kaingineros and adoption of permanent forms of agriculture that are not suited for the uplands. In turn, kaingin is coercively regulated with fines or jail time, while indigenous upland farmers are frequently harassed by forest guards”.

In 1994, a ban against shifting cultivation (bawal sa kaingin) was enforced by former Mayor Edward Hagedorn through the so called ‘bantay gubat’: an implementing arm composed of poorly trained forest guards. When this happened, no murmur of dissent was raised by Palawan NGOs, in spite of the severe hardship experienced by hundreds of indigenous communities because of the ban. The latter, however, was strongly opposed by Survival International (SI), the global movement for tribal peoples' rights. The international campaign by Survival International resulted in a partial lifting of the ban. Apparently, at the end, the former Mayor decided to allow Batak as well as Tagbanua tribes to continue their traditional kaingin practices with a ‘controlled burning’ rather than the previous ‘zero burning’ policy. However – as the years passed by – the ‘ban on kaingin’ was imposed again with vigor and is now being implemented under the current administration "Ever since the ban on shifting cultivation was implemented in PPC Municipality, Survival has been lobbying for the government to exempt indigenous communities, such as the Batak, from the ban” says Sophie Grig, Senior Campaigner at Survival International. "We are disappointed that in spite of international pressure, the local government still continues to implement a law which is creating food-shortage and malnutrition amongst the previously self-sufficient tribes of Northern Palawan". In spite of its failure, the ‘ban on kaingin’ initially implemented in Puerto Princesa Municipality, is now being emulated by others. Recently, the Government of Brooke’s Point has proposed the implementation of similar restrictions in its own municipality and, if the ban will push through, hundreds of upland Pala’wan communities will be threatened with food insecurity and malnourishment.

The CS aerial survey has added more fuel to the fire, through the production of dramatic photos--- images that, however, lack of context. These images have prompted Governor Jose Alvarez to declare war on kaingin by proposing the creation of a ‘forest conservation task force that will undertake a 10-year plan to arrest the problem of slash-and-burn farming’. “We are extremely worried about these new developments” says John Mart Salunday an indigenous Tagbanua who is presiding NATRIPAL, the largest indigenous federation in Palawan. “There are several indigenous communities’ conserved areas (ICCAs) in our province where traditional kaingin has been sustainably practiced from generations to generations.

Unfortunately, the 'anti-kaingin policy' and the ‘bantay gubat’ implementing it, make no distinction between unsustainable 'kaingin' done by Filipino migrants and the traditional 'kaingin' still practiced by many indigenous people.” says Salunday. “Upland rice is such a strong part of our identify and our people have selected more than 80 varieties of rice over hundreds of years, not to mention the diversity of other crops: cassava, ubi, sweet potatoes, banana and many others. If all this is taken away from us, our tribes will have no future” he adds.

The richness and complexity of indigenous upland farming systems in Palawan has not gone unnoticed to both local and foreign researchers such as Roy Cadelina, James Eder, Melanie McDermott, Nicole Revel, Charles Macdonald, Wolfram Dressler and Dario Novellino who have carried out in-depth studies on indigenous farming practices and on their relevance in people’s cosmologies, worldviews, identities and ethnobiological knowledge. “If one compares the wisdom of indigenous upland farmers to the ignorance of most foresters, politicians and conservation biologists in the same field of knowledge, the gap is striking” says Dario Novellino, an anthropologist of the Centre for Biocultural Diversity of the University of Kent (UK) who has lived in Palawan over a period of almost 30 years. He sustains that the government ban on kaingin, implemented in Puerto Princesa, rather than protecting the environment, has placed insurmountable pressure on the forest and has also altered the sustainability of the indigenous farming system. “I have see forest guards (bantay gubat) advising indigenous farmers to cut only very small trees for their ‘uma’ (upland fields) and to cultivate the same plots of land continuously” says Novellino “these indications are based on a very poor understanding of forest ecology. If you clear areas where only small trees are found, it means that you are going to plant land that has not yet regenerated its soil nutrients. When you cultivate these fragile soils, over and over, you cause them to become infertile. Ultimately, only cogun (Imperata cylindrica) will thrive in these areas and the forest will never grow back”.

Well-known scholars have argued that traditionally practiced kaingin (or integral kaingin) involves the intermittent clearing of small patches of forest for subsistence food crop production, followed by longer periods of fallow in which forest re-growth restores productivity to the land. “Kaingin can yield complex assemblages of forest and other vegetation in unique mosaics comprised of open canopy tree associations to mature closed-canopy forest systems best understood at the landscape scale. As a complex system of agriculture and forestry, integrating production from cultivated fields and diverse secondary forests, kaingin farming may yield a wide range of ecosystem services and resources integral to livelihoods and forest environments in the mountains of Palawan” says Dressler. However, when such a complex system is altered, as for instance, due to the implementation of punitive policies, the repercussions on forest ecology and people’s sustenance becomes dramatic. According to Novellino, when indigenous upland communities are not allowed to procure part of the needed ‘carbohydrates’ (rice, cassava, sweet potatoes, etc.) through their farming practices, they are forced, as a result, to increase pressure on commercially valuable NTFPs (rattan, almaciga and honey) which they sell to purchase rice. Ultimately, this may result in the fast depletion of non-timber forest resources and more pressure on the forest itself. Indeed, this is exactly what has happened because of the implementation of the ‘zero burning policy’ by former Mayor Edward Hagedorn.

One can only speculate why the Government of Palawan is so quick in raising its voice against kaingin while, on the other hand, remains silence when huge expanses of land, forest and fertile grounds are given away for agribusinesses. But, at least, we know the official explanation: oil palms are only planted on ‘idle’ and ‘abandoned’ land to enhance the province’s economy while increasing job opportunities and transforming unused areas in productive plantations. But are such lands really ‘idle’ and ‘abandoned’? A recent study carried out by ALDAW (Ancestral Land/Domain Watch) has clearly proven the contrary. The study argues that most of these so called 'idle' and 'unproductive' lands include areas that have been used since time immemorial by IPs societies. “The removal of natural vegetation and of previous agricultural improvements by oil palm plantations is leading to the total collapse of traditional livelihoods, thus fostering communities’ impoverishment and increasing malnutrition” says Novellino. He sustains that what the Government has failed to consider is that most of the so called ‘idle’ and ‘underdeveloped’ lands include areas that are being utilized by rural and indigenous populations for different purposes (gathering of non-timber forest products (NTFPs), medicinal plants, kaingin, etc). He believes that a direct relationship exists between oil palm/cash crop expansion, the impoverishment of people’s diet, the progressive deterioration of traditional livelihood and the interruption of cultural transmission related to particular aspects of people’s local knowledge.

As argued by Dressler “In contrast to commercially oriented monocultures, mixed swidden systems benefit Palawan’s indigenous peoples by offering a variety of timber and non-timber harvests for subsistence and commercial sales to diversify production and spread risks, thus avoiding the ecological and economic shocks associated with relying on one product too heavily”. Apparently, this is not perceived by the Government as a sufficiently strong reason to switch its development agenda towards more sustainable forms of agriculture. Instead, local food security continues to be sacrificed in the name of oil palm and rubber development while anti-kaingin policies are strongly implemented with no distinction between traditional indigenous farming practices and migrants’ unsustainable slash-and-burning. “If the government is serious about ensuring the welfare of its constituents” says Welly Mande a Tagbanua of CALG “ it should enhance the capability of upland farmers to produce enough food, rather than fostering cash crop such as oil palms and rubber that are not for local consumption but for export”. “What we would need instead” adds Mandi “are lower risk models of agricultural development that give a greater share of benefits to the poor while improving and fostering the production of endemic crops such as coconuts and rice”.

For the sake of fairness, we should now ask ourselves whether, at the present, all indigenous shifting cultivation practices throughout Palawan are always sustainable (based on long fallow periods). The answer is NO but, again, the blame for forest destruction should not be placed on upland dwellers. Perhaps, one should look instead at the historical process that have led to unsustainable kaingin practices such as the dramatic reduction of indigenous ancestral domains due to massive migration of landless farmers, encroachment by mining and plantation companies, insurgency and militarization just to mention few.

Official propaganda against kaingin, coupled by NGOs’ market-based conservation approaches, continues to provide additional incentives for international institutions to finance more of the same (e.g. reforestation of indigenous fallow fields which are wrongly classified as ‘degraded areas’). Often, such reforestation programs deprive local communities of those areas that are necessary for fields’ rotation, hence jeopardizes the sustainability of their farming system.

It will require detailed and multidisciplinary studies to determine where, and to what extent, the conditions for optimal long fallows in Palawan are still present and how many indigenous communities are still practicing long rotation cycles. In turn, the law should move away from coercion and demonization of kaingin towards more culturally sensitive approaches that provide incentives to indigenous cultivators for increasing and fostering production of local genetic varieties or rice and other traditional cultivars. In places where swidden practices have become irreversibly unsustainable, specific strategies should be developed in close coordination with local communities, rather than imposing top-down technical solutions and enforce legal persecution. In short, upland farming strategies should be evaluated through an integrated and interactive long-term process of research and development in close partnership with local upland farmers. This process should identify indigenous best farming practices, understanding them and the contexts in which these are used. Meanwhile, in the short term, it would work better if some media would refrain from publishing images that uncritically depict upland dwellers as ‘environmental criminals’, putting the blame of deforestation on those who suffers from it most.

Recent years have seen an exponential increase in land deals across the Philippines with the conversion of large expanses of land with crops mainly intended for export while traditional upland farming implemented through swidden (‘slash-and-burn’) technology (kaingin) is demonized and antagonized through restrictive legislation. The latter, however, fosters local self-sufficiency and plays a fundamental role in the livelihood and worldviews of indigenous societies.

|

| AGUMIL/PPVOMI oil palm expansion in Bataraza, Palawan |

The Inquirer’s article was triggered by an aerial survey carried out by the Center for Sustainability (CS), a nonprofit organization claiming to work for sustainable development in Palawan. The group spotted from the air key locations, previously covered by forest, and which have now been subject to clearing due to various external forces (mining, oil palm plantations and shifting agriculture (locally known as kaingin, or more appropriately ‘uma’). According to the group, in addition to clearing by ‘poor farmers’, forest burning in the south has been linked to the proliferation of palm oil and rubber plantations, and the main target of ‘slash-and-burn’ activities is the clearing of primary forests for development.

Ironically, for carrying out its photo survey CS conservationists alegedly borrowed the private plane of Jose Alvarez, the present Governor of Palawan, a well-known supporter of large-scale agro-industry, especially rubber which accelerates deforestation and deprives more traditional indigenous communities of their resource-base. He is chairing the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD). In principle, this government body is mandated to ensure the sustainable development of the whole province, through the implementation of the Strategic Environmental Plan – SEP (R.A. Republic Act 7611). The latter mandates that no development project should take place in Palawan unless the proponents secure the so called SEP clearance. Surprisingly, as of now, massive oil palm expansion and related forest clearing have taken placed unabated without SEP clearances. “Here in Palawan” says Marivic Bero (Secretary General of the Coalition against Land Grabbing - CALG). “We have the best laws in place to protect both the environment and the rights of our indigenous peoples. However, the limits of law lay within the implementation process, wherein rules and regulations are conditioned by the inability of concerned government agencies and their officials to stand by their own mandates”. She further argues that the government prohibition to ban kaingin represents a blatant violation of the major tenets of the ‘Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997’ (Republic Act no. 8371) which recognizes, protects and promotes the rights of indigenous cultural communalities. “This is a very powerful law” says Bero “and should not be undermined by ‘minor’ laws and municipal ordinances banning shifting cultivation (kaingin)”.

While Palawan environment is being affected by agribusiness (mainly oil palm and rubber), mining enterprises - and various forms of land grabbing - state agencies such as PCSD (as well as some Palawan NGOs) still view indigenous kaingin as ‘illegitimate agriculture’ and as the primary cause of deforestation. “Turning a blind eye to the plunder of forests by industrial logging, mining activities, agribusiness, and livestock production, state agencies continue to label and classify kaingin farmers as primitive, backward and unproductive who waste valuable forest resources, particularly timber” says Dressler. “In this way”, he adds “Government agencies have unleashed anti-kaingin campaigns that justified the resettling of kaingineros and adoption of permanent forms of agriculture that are not suited for the uplands. In turn, kaingin is coercively regulated with fines or jail time, while indigenous upland farmers are frequently harassed by forest guards”.

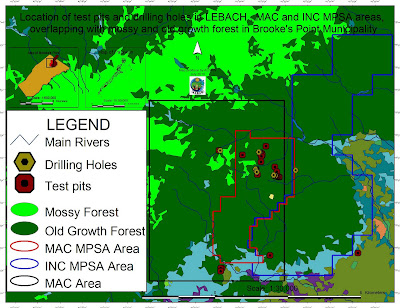

In 1994, a ban against shifting cultivation (bawal sa kaingin) was enforced by former Mayor Edward Hagedorn through the so called ‘bantay gubat’: an implementing arm composed of poorly trained forest guards. When this happened, no murmur of dissent was raised by Palawan NGOs, in spite of the severe hardship experienced by hundreds of indigenous communities because of the ban. The latter, however, was strongly opposed by Survival International (SI), the global movement for tribal peoples' rights. The international campaign by Survival International resulted in a partial lifting of the ban. Apparently, at the end, the former Mayor decided to allow Batak as well as Tagbanua tribes to continue their traditional kaingin practices with a ‘controlled burning’ rather than the previous ‘zero burning’ policy. However – as the years passed by – the ‘ban on kaingin’ was imposed again with vigor and is now being implemented under the current administration "Ever since the ban on shifting cultivation was implemented in PPC Municipality, Survival has been lobbying for the government to exempt indigenous communities, such as the Batak, from the ban” says Sophie Grig, Senior Campaigner at Survival International. "We are disappointed that in spite of international pressure, the local government still continues to implement a law which is creating food-shortage and malnutrition amongst the previously self-sufficient tribes of Northern Palawan". In spite of its failure, the ‘ban on kaingin’ initially implemented in Puerto Princesa Municipality, is now being emulated by others. Recently, the Government of Brooke’s Point has proposed the implementation of similar restrictions in its own municipality and, if the ban will push through, hundreds of upland Pala’wan communities will be threatened with food insecurity and malnourishment.

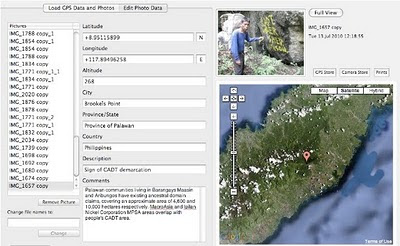

|

| Geotagging of a mountain range within MMPL used sustainably by upland Pala’wan since time immemorial |

|

| Batak girl harvesting new upland rice |

The richness and complexity of indigenous upland farming systems in Palawan has not gone unnoticed to both local and foreign researchers such as Roy Cadelina, James Eder, Melanie McDermott, Nicole Revel, Charles Macdonald, Wolfram Dressler and Dario Novellino who have carried out in-depth studies on indigenous farming practices and on their relevance in people’s cosmologies, worldviews, identities and ethnobiological knowledge. “If one compares the wisdom of indigenous upland farmers to the ignorance of most foresters, politicians and conservation biologists in the same field of knowledge, the gap is striking” says Dario Novellino, an anthropologist of the Centre for Biocultural Diversity of the University of Kent (UK) who has lived in Palawan over a period of almost 30 years. He sustains that the government ban on kaingin, implemented in Puerto Princesa, rather than protecting the environment, has placed insurmountable pressure on the forest and has also altered the sustainability of the indigenous farming system. “I have see forest guards (bantay gubat) advising indigenous farmers to cut only very small trees for their ‘uma’ (upland fields) and to cultivate the same plots of land continuously” says Novellino “these indications are based on a very poor understanding of forest ecology. If you clear areas where only small trees are found, it means that you are going to plant land that has not yet regenerated its soil nutrients. When you cultivate these fragile soils, over and over, you cause them to become infertile. Ultimately, only cogun (Imperata cylindrica) will thrive in these areas and the forest will never grow back”.

|

| Pala’wan horticulturists in the uplands of Brookes’ Point Municipality |

|

| Mining concessions in Palawan |

As argued by Dressler “In contrast to commercially oriented monocultures, mixed swidden systems benefit Palawan’s indigenous peoples by offering a variety of timber and non-timber harvests for subsistence and commercial sales to diversify production and spread risks, thus avoiding the ecological and economic shocks associated with relying on one product too heavily”. Apparently, this is not perceived by the Government as a sufficiently strong reason to switch its development agenda towards more sustainable forms of agriculture. Instead, local food security continues to be sacrificed in the name of oil palm and rubber development while anti-kaingin policies are strongly implemented with no distinction between traditional indigenous farming practices and migrants’ unsustainable slash-and-burning. “If the government is serious about ensuring the welfare of its constituents” says Welly Mande a Tagbanua of CALG “ it should enhance the capability of upland farmers to produce enough food, rather than fostering cash crop such as oil palms and rubber that are not for local consumption but for export”. “What we would need instead” adds Mandi “are lower risk models of agricultural development that give a greater share of benefits to the poor while improving and fostering the production of endemic crops such as coconuts and rice”.

For the sake of fairness, we should now ask ourselves whether, at the present, all indigenous shifting cultivation practices throughout Palawan are always sustainable (based on long fallow periods). The answer is NO but, again, the blame for forest destruction should not be placed on upland dwellers. Perhaps, one should look instead at the historical process that have led to unsustainable kaingin practices such as the dramatic reduction of indigenous ancestral domains due to massive migration of landless farmers, encroachment by mining and plantation companies, insurgency and militarization just to mention few.

Official propaganda against kaingin, coupled by NGOs’ market-based conservation approaches, continues to provide additional incentives for international institutions to finance more of the same (e.g. reforestation of indigenous fallow fields which are wrongly classified as ‘degraded areas’). Often, such reforestation programs deprive local communities of those areas that are necessary for fields’ rotation, hence jeopardizes the sustainability of their farming system.

It will require detailed and multidisciplinary studies to determine where, and to what extent, the conditions for optimal long fallows in Palawan are still present and how many indigenous communities are still practicing long rotation cycles. In turn, the law should move away from coercion and demonization of kaingin towards more culturally sensitive approaches that provide incentives to indigenous cultivators for increasing and fostering production of local genetic varieties or rice and other traditional cultivars. In places where swidden practices have become irreversibly unsustainable, specific strategies should be developed in close coordination with local communities, rather than imposing top-down technical solutions and enforce legal persecution. In short, upland farming strategies should be evaluated through an integrated and interactive long-term process of research and development in close partnership with local upland farmers. This process should identify indigenous best farming practices, understanding them and the contexts in which these are used. Meanwhile, in the short term, it would work better if some media would refrain from publishing images that uncritically depict upland dwellers as ‘environmental criminals’, putting the blame of deforestation on those who suffers from it most.