By ALDAW Network (Ancestral Land/Domain Watch): Between June and August 2009, an ALDAW mission travelled to the Municipalities of Brooke’s Point and Sofronio Española (Province of Palawan) to carry out field reconnaissance and audio-visual documentation on the social and ecological impact of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) plantations. The mission’s primary task focused on two major objectives: 1) gathering data through interviews, ocular inspection and participatory geographic information systems methodologies; 2) providing communities with detailed information on the ecological and social impact of oil palm plantations, to allow them to make informed decisions while confronting oil palm companies, state laws and bureaucracy.

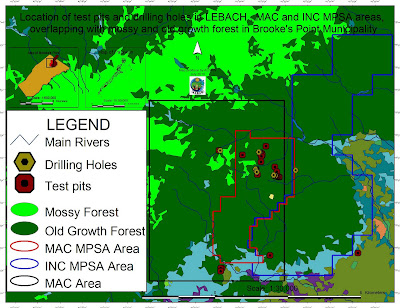

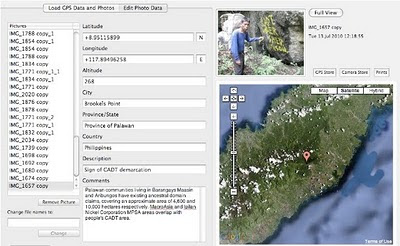

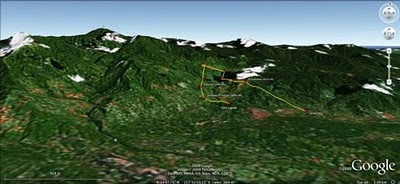

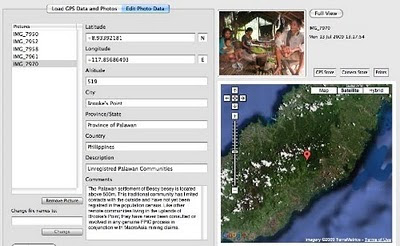

Successive ALDAW field appraisals in oil palm impacted areas took place between July 2010 and early 2013, and included the Municipalities of Aborlan, Rizal and Quezon. During ALDAW field research, GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of a professional device connected to the camera’s hot shoe.

The geotagged images have been loaded into a geo-aware application and displayed on satellite Google map. The actual ‘matching’ of GPS data to photographs has revealed that, in specific locations, oil palm plantations are expanding at the expenses of primary and secondary forest and are competing with pre-existing cultivations (coconut groves, fruit tress, wet-rice, etc).

The conversion of productive paddy land and forest into oil palm plantations is particularly evident in the Municipality of Quezon .

Oil palm plantations have also expanded in areas used by indigenous people for the cultivation of local varieties of upland rice, root crops and fruit trees. Furthermore, the fencing of large areas of oil palm plantations makes it difficult for local communities to reach their upland fields and forest.

Oil palm plantations have also expanded in areas used by indigenous people for the cultivation of local varieties of upland rice, root crops and fruit trees. Furthermore, the fencing of large areas of oil palm plantations makes it difficult for local communities to reach their upland fields and forest.

Geottaged evidences have also revealed the exact location of commonly used NTFPs, such as buri palms (Corypa elata) and bamboos that are being destroyed through massive land clearing by oil palm companies.

Moreover, geocoded photos have provided indications on the location of rivers and freshwater sources that are being incorporated into oil palm plantations and that are likely to become polluted through the use of pesticides and fertilizers.

These freshwater sources provide potable water for local communities and some of them are essential for the maintenance of community-based dams.

Initial steps are now being taken to establish collaborative exchanges between the oil palm impacted indigenous communities of Palawan and those of Mindanao which are facing a similar fate. These exchanges and cross-visits will include training courses on geotagging and participatory videos done by indigenous peoples (ALDAW staff) to other indigenous groups such as the Higaonon of Bukidnon. In addition to this, during such cross-visits, common advocacy strategies to resist oil palm expansion nationwide will be identified.

In response to recent research findings, see Palawan Oil Palm Geotagged Report 2013 (Part 1 and Part 2)

ALDAW has launched two major campaign initiatives:

Successive ALDAW field appraisals in oil palm impacted areas took place between July 2010 and early 2013, and included the Municipalities of Aborlan, Rizal and Quezon. During ALDAW field research, GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of a professional device connected to the camera’s hot shoe.

The geotagged images have been loaded into a geo-aware application and displayed on satellite Google map. The actual ‘matching’ of GPS data to photographs has revealed that, in specific locations, oil palm plantations are expanding at the expenses of primary and secondary forest and are competing with pre-existing cultivations (coconut groves, fruit tress, wet-rice, etc).

The conversion of productive paddy land and forest into oil palm plantations is particularly evident in the Municipality of Quezon .

Oil palm plantations have also expanded in areas used by indigenous people for the cultivation of local varieties of upland rice, root crops and fruit trees. Furthermore, the fencing of large areas of oil palm plantations makes it difficult for local communities to reach their upland fields and forest.

Oil palm plantations have also expanded in areas used by indigenous people for the cultivation of local varieties of upland rice, root crops and fruit trees. Furthermore, the fencing of large areas of oil palm plantations makes it difficult for local communities to reach their upland fields and forest. Geottaged evidences have also revealed the exact location of commonly used NTFPs, such as buri palms (Corypa elata) and bamboos that are being destroyed through massive land clearing by oil palm companies.

Moreover, geocoded photos have provided indications on the location of rivers and freshwater sources that are being incorporated into oil palm plantations and that are likely to become polluted through the use of pesticides and fertilizers.

These freshwater sources provide potable water for local communities and some of them are essential for the maintenance of community-based dams.

Initial steps are now being taken to establish collaborative exchanges between the oil palm impacted indigenous communities of Palawan and those of Mindanao which are facing a similar fate. These exchanges and cross-visits will include training courses on geotagging and participatory videos done by indigenous peoples (ALDAW staff) to other indigenous groups such as the Higaonon of Bukidnon. In addition to this, during such cross-visits, common advocacy strategies to resist oil palm expansion nationwide will be identified.

In response to recent research findings, see Palawan Oil Palm Geotagged Report 2013 (Part 1 and Part 2)

ALDAW has launched two major campaign initiatives:

- Petition 1 (covers Palawan and Mindanao, addressed to the National Government)

- Petition 2 (covers Palawan specifically, addressed towards the Provincial Government, the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) and the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP)