Showing posts with label geotagging. Show all posts

Showing posts with label geotagging. Show all posts

Monday, November 22, 2010

The Power of Geographic Information

The Centre of GIS & Remote Sensing (SIGTE) of the University of Girona, presents “The Power of Geographic Information”.

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Oil Palm Expansion: A New Threat to Palawan UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve

ALDAW, Puerto Princesa - In addition to the alarming expansion of nickel mining on Palawan island (already reported on previous PLANT TALKS releases) indigenous peoples are now being confronted with the threats posed by the expansion of oil palm plantations. The province of Palawan is part of the “Man and Biosphere Reserve” program of UNESCO and hosts 49 animals and 56 botanical species found in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. It is also the home of isolated and vanishing indigenous communities.

Agrofuels in Palawan, as elsewhere in the Philippines, have been portrayed as a key solution to lower greenhouse gas emission, achieve energy independence, as well as a tool for poverty eradication. With these objects in mind, the Provincial Government of Palawan is strongly promoting agrofuels development, without taking into account the socio-ecological impact of such mono-crop plantations. As a result, thousands of hectares of lands in the province have been set aside for jatropha feedstock and oil palm.

Oil palm plantations, in Palawan, are being established by the Agumil Philippines Inc., a joint venture between Filipino and Malaysian investors, that also engages in the processing of palm oil. The LandBank of the Philippines is backing the project financially.

The local indigenous network ALDAW (Ancestral Land Domain Watch), in collaboration with other local organizations and Palawan NGOs, is making a call for the implementation of more restrictive regulations on oil palm expansion to halt deforestation, habitat destruction, food scarcity, and violation of indigenous peoples’ rights. In addition to this, oil palm plantations are also expanding into the indigenous fallow land (benglay), thus reducing the number of rotational areas needed for the swidden cycle. As of now, the Palawan municipality of Española has the highest percentage of oil palms, and plantations are fast expanding also to other municipalities such as Brooke’s Point, Bataraza, Rizal, Quezon, etc. In some municipalities, oil palms are already competing and taking over cultivated areas (e.g. rice fields), which are sustaining local self-sufficiency.

“LandBank’s contribution to President Aquino’s commitment to develop the rural economy and to raise farmers’ income should not include oil palms development. It is well known that this crop benefits better-off farmers and entrepreneurs, rather then small-scale farmers and indigenous peoples. We look forward to more sustainable investments for improving agricultural productivity of marginalized farmers. Meanwhile, a moratorium on oil palm expansion should be implemented with haste” said Artiso Mandawa, ALDAW Chairman.

“LandBank’s contribution to President Aquino’s commitment to develop the rural economy and to raise farmers’ income should not include oil palms development. It is well known that this crop benefits better-off farmers and entrepreneurs, rather then small-scale farmers and indigenous peoples. We look forward to more sustainable investments for improving agricultural productivity of marginalized farmers. Meanwhile, a moratorium on oil palm expansion should be implemented with haste” said Artiso Mandawa, ALDAW Chairman.

In the community of Iraray II (Municipality of Española) indigenous people complain that a ‘new’ pest has spread from the neighboring oil palm plantations to their cultivated fields devouring hundreds of coconut palms by boring large networks of tiny tunnels into the palms’ trunks. Local indigenous people showed specimens of this pest to ALDAW mission members, and the insect was later identified as the Red Palm Weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus). The red weevil is reported to be a native of south Asia, however, the Palawan of Iraray II claims that they only began to experience massive pest attacks on their coconut groves, after oil palms were introduced into the area at the expense of the local population of buri palms (Corypha elata). The latter is a popular basketry material for both the local Palawan and farmer communities. The trunk of this palm contains edible starch. The bud (ubud) is also edible raw or cooked, as well as the kernels of the nuts.

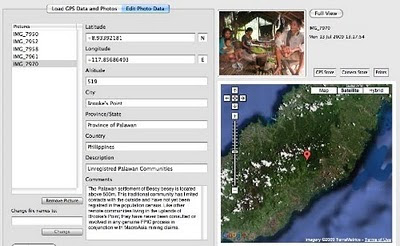

ALDAW preliminary findings, obtained in collaboration with the Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) – University of Kent, indicate there is a scarcity of public records showing the processes and procedures leading to the issuance of land conversion permits and environmental clearances to oil palm companies, as well as to the local cooperatives created in the various barangays. Moreover, ALDAW is also in the process of mapping all oil palm locations in Palawan, through the use of geotagging technologies. Evidence indicates that – in most cases - members of indigenous communities, who have ‘rented’ portions of their land to the oil company, have no clear understanding of the nature of such ‘agreements’ nor they possess written contracts countersigned by the company. There is a risk that members of local communities who have joined the so-called ‘cooperatives’ will soon become indebted with the oil company. In fact they provide very cheap labor and also barrow funds to purchase fertilizer, pesticides and equipment, while the company controls every aspect of production.

Overall, it would appear that land conversion into oil palm plantations is happening with little or no monitoring on the part of those government agencies (e.g. Palawan Council for Sustainable Development) that are responsible for the sustainable management of the Province.

The new trend in the Philippine Market: switching from coconut to palm oil

There is a new trend in the Philippines, leading to the acceleration of oil palm expansion. National vegetable oil millers and refiners are now keen on selling the cheaper palm oil for the domestic market, so that all coconut oil would be exported. Coconut oil, in fact, commands a higher premium in the international market. However, contrary to oil palms, coconut cultivation is endemic to the Philippines and this palm provides multiple products to local farmers, thus sustaining household based economy.

Since 2005, cooking oil manufacturers have increased imports of the cheap palm oil by 90 percent. The use of the palm oil has progressively increased in the local market as household consumers and institutional buyers have preferred it because of the price difference compared with edible coconut oil. Fast-food giants such as Jollibee Foods Corp., have switched to palm oil for their business.

The General Context of Oil Palm Development

Crude palm oil (CPO) consumption worldwide has doubled between 2000 and 2010 with the main new demand coming from Eastern Europe, India and China. By and large, the price of palm oil has increased almost steadily over the past 20 years. Two countries in South East Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia, produce over 80% of the internationally traded CPO. While significant expansion is occurring in Thailand, Papua New Guinea, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo and it is now taking over in the Philippines. Currently there are an estimated 4 million hectares of land under oil palms in Malaysia and over 7.5 million hectares in Indonesia. In Peninsular Malaysia, the palm oil frontier has come near to the limits of land availability and most expansion within Malaysia is now in the two Eastern States of Sabah and Sarawak. Much of the investment for oil palm expansion has come from European Banks but, increasingly, funds are being raised from Islamic banks in the Middle East, and from investors from India and China. It has been estimated that about two thirds of the companies opening lands to plant oil palm in Indonesia are majority-owned by Malaysian conglomerates

The economies of scale and the characteristics of oil palm favor the development of large plantations, meaning that land needs to be acquired in large blocks and huge areas converted to monocultures. Obviously, this pressure to acquire land has implications for those who currently own the same areas, who are for the most part ‘indigenous peoples’ and small household farmers. Since 2004, international and local NGOs have produced a series of detailed reports based on field surveys and the direct testimony of affected people, which document the serious human rights abuses resulting from the imposition of oil palm plantations. The publications show that these abuses are widespread, are inherent in the way lands are acquired and estates are developed and continue up to the present day. Among the most persistent problems are the following: acquisition of lands and smallholder schemes violates the rights of indigenous peoples to their property. Their lands are being taken off them without due payment and without remedy. In addition, their right to give or withhold their free, prior and informed consent for these proposed developments is being violated. In Indonesia, those that sign up to join imposed schemes are not informed that this reallocation of lands implies a permanent surrender of their rights in land. The dramatic changes in local landscapes and ecosystems - including the loss of agricultural and agroforestry lands, hunting grounds, game, fish, forests, as well as water for drinking, cooking and bathing - in turn have major consequences and deprive people of their customary livelihoods and means of subsistence.

Unfair processes of land use allocation and land acquisition and the lack of respect for local communities and indigenous peoples’ rights not only result in marginalization and impoverishment but also give rise to long term disputes over land, which all too often escalate into conflicts with concomitant human rights abuses due to repressive actions by company or State security forces.

Generally, when large agricultural firms enter an area, community members loose access to traditional food zones and other NTFP resources. As a result, they end up becoming employers of oil palm plantations. Lacking legal title to their land, deals are often structured so that members of the community acquire 2-3 hectares (508 acres) of land for oil palm cultivation. In Borneo (Eastern Malaysia and Kalimantan) they typically borrow some $3,000-6,000 (at 30 percent interest per year) from the parent firm for the seedlings, fertilizers, and other supplies. Because oil palm takes roughly 7 years to bear fruit, they work as day laborers at $2.50 per day on mature plantations. In the meantime their plot generates no income but requires fertilizers and pesticides, which are purchased from the oil palm company. Once their plantation becomes productive, the average income for a 2 hectare allotment is $682-900 per month. In the past, rubber and wood generated $350-1000 month (see Lisa Curran studies and WWF Germany reports).

Loss of Biodiversity

As of now, scientific evidence indicates that beyond the obvious deforestation that results from clearing lowland rainforest for plantations, there is a significant reduction (on the order of 80 percent for plants and 80-90 percent for mammals, birds, and reptiles) in biological diversity following forest conversion to oil palm plantation. Moreover, the use of herbicides and pesticides used in oil palm plantations heavily pollutes local waterways. Notoriously, further destruction of peat land has increases the risk of flooding and fire.

The Legal Framework

The legal frameworks in the world’s two foremost palm oil producing countries are inappropriate to protect indigenous peoples’ rights and ensure an equitable development process. In spite of innovative environmental and pro-indigenous legislation, also in the Philippines the issue of oil palm expansion with reference to farmers and indigenous peoples’ rights does show a high degree of paucity.

International organizations have begun to pin their hopes of reform on the creation of a global market in carbon to curb deforestation, although whether this will help or harm indigenous peoples is a matter of debate. Indeed, initial calculations based on current prices, in the voluntary carbon trading market, suggest that market-based payments for Reducing in Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) will not be enough by themselves to make economies based on maintaining natural forests competitive with oil palm. If, however, there is to be a real moratorium on land clearance then this may provide an important opportunity for the Government to effect reforms in the forestry and plantations sectors, take firm steps to amend the laws so they recognize indigenous peoples’ rights and adopt a more measured approach to rural development that gives priority to local communities’ initiatives and not the interests of foreign backed companies.

In the international arena, civil society is presently engaging with processes of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which is an initiative established by businesses involved in the production, processing and retail of oil palm and WWF. Key members include Malaysian and Indonesian palm oil companies and European processing and retailing companies. RSPO is attempting to agree and apply an industry best practice standard for the production and use of palm oil in socially and environmentally acceptable ways. Civil society engagement in this process has secured: 1) the establishment of the RSPO Task Force on Smallholders, which has Developed Guidance to ensure smallholder engagement; 2) strong social protections and requirements for respect for the rights of indigenous peoples, workers, women in the RSPO Principles and Criteria (the standard); and 3) a certification process that is meant to ensure adherence to the standard.

However, there are major concerns about this process, such as the growing concern that RSPO members are operating to double standards, most indigenous peoples and local communities and smallholders remain unaware of the RSPO and are still unclear how they can use it to secure their rights and fair development outcomes. Wider awareness needs to be fostered among NGOs to build on the gains, if any, being made at the RSPO, among others. To date, sustained civil society engagement with the industry and national dialogues about oil palm have been limited to Indonesia and to a lesser extent Malaysia. In the Philippines, local actions in addressing oil palm issues have so far been limited and thus, there is a need for greater sharing and concerted action at the local/national and regional levels.

* Section of this report have been extracted from Forest People Programme (FPP) report: “Palm oil and indigenous peoples in South East Asia. Land acquisition, human rights violations and indigenous peoples on the palm oil frontier” by Marcus Colchester. Other sources: The Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), RECOFTC, Sawit Watch, the Samdhana Institute, Dr. Lisa M. Curran, School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, WWF Germany.

What you can do:

Sign the online Petition to Stop Mining and Oil Palm Expansion in Palawan

And address your concerns to:

*PALAWAN COUNCIL FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (PCSD)

oed@pcsd.ph . AND c/o Mearl Hilario mearlhilario@yahoo.com

FAX: 0063 (048) 434-4234

*Honorable Governor of Palawan

Baham Mitra

abmitra2001@yahoo.com FAX: 0063 (048) 433-2948

*Palawan Project Manager

Agumil Philippines, Inc

Agusan Plantations Group. Fax 0063 323444884

*Mrs. Gilda E. Pico, President and CEO, Land Bank of the Philippines

landbank@mail.landbank.com Fax: 0063 2 528-8580

or contact the ALDAW Network (Ancestral Land/Domain Watch) aldawnetwork@gmail.com

Source: ALDAW Network

Agrofuels in Palawan, as elsewhere in the Philippines, have been portrayed as a key solution to lower greenhouse gas emission, achieve energy independence, as well as a tool for poverty eradication. With these objects in mind, the Provincial Government of Palawan is strongly promoting agrofuels development, without taking into account the socio-ecological impact of such mono-crop plantations. As a result, thousands of hectares of lands in the province have been set aside for jatropha feedstock and oil palm.

Oil palm plantations, in Palawan, are being established by the Agumil Philippines Inc., a joint venture between Filipino and Malaysian investors, that also engages in the processing of palm oil. The LandBank of the Philippines is backing the project financially.

The local indigenous network ALDAW (Ancestral Land Domain Watch), in collaboration with other local organizations and Palawan NGOs, is making a call for the implementation of more restrictive regulations on oil palm expansion to halt deforestation, habitat destruction, food scarcity, and violation of indigenous peoples’ rights. In addition to this, oil palm plantations are also expanding into the indigenous fallow land (benglay), thus reducing the number of rotational areas needed for the swidden cycle. As of now, the Palawan municipality of Española has the highest percentage of oil palms, and plantations are fast expanding also to other municipalities such as Brooke’s Point, Bataraza, Rizal, Quezon, etc. In some municipalities, oil palms are already competing and taking over cultivated areas (e.g. rice fields), which are sustaining local self-sufficiency.

“LandBank’s contribution to President Aquino’s commitment to develop the rural economy and to raise farmers’ income should not include oil palms development. It is well known that this crop benefits better-off farmers and entrepreneurs, rather then small-scale farmers and indigenous peoples. We look forward to more sustainable investments for improving agricultural productivity of marginalized farmers. Meanwhile, a moratorium on oil palm expansion should be implemented with haste” said Artiso Mandawa, ALDAW Chairman.

“LandBank’s contribution to President Aquino’s commitment to develop the rural economy and to raise farmers’ income should not include oil palms development. It is well known that this crop benefits better-off farmers and entrepreneurs, rather then small-scale farmers and indigenous peoples. We look forward to more sustainable investments for improving agricultural productivity of marginalized farmers. Meanwhile, a moratorium on oil palm expansion should be implemented with haste” said Artiso Mandawa, ALDAW Chairman.In the community of Iraray II (Municipality of Española) indigenous people complain that a ‘new’ pest has spread from the neighboring oil palm plantations to their cultivated fields devouring hundreds of coconut palms by boring large networks of tiny tunnels into the palms’ trunks. Local indigenous people showed specimens of this pest to ALDAW mission members, and the insect was later identified as the Red Palm Weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus). The red weevil is reported to be a native of south Asia, however, the Palawan of Iraray II claims that they only began to experience massive pest attacks on their coconut groves, after oil palms were introduced into the area at the expense of the local population of buri palms (Corypha elata). The latter is a popular basketry material for both the local Palawan and farmer communities. The trunk of this palm contains edible starch. The bud (ubud) is also edible raw or cooked, as well as the kernels of the nuts.

ALDAW preliminary findings, obtained in collaboration with the Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) – University of Kent, indicate there is a scarcity of public records showing the processes and procedures leading to the issuance of land conversion permits and environmental clearances to oil palm companies, as well as to the local cooperatives created in the various barangays. Moreover, ALDAW is also in the process of mapping all oil palm locations in Palawan, through the use of geotagging technologies. Evidence indicates that – in most cases - members of indigenous communities, who have ‘rented’ portions of their land to the oil company, have no clear understanding of the nature of such ‘agreements’ nor they possess written contracts countersigned by the company. There is a risk that members of local communities who have joined the so-called ‘cooperatives’ will soon become indebted with the oil company. In fact they provide very cheap labor and also barrow funds to purchase fertilizer, pesticides and equipment, while the company controls every aspect of production.

Overall, it would appear that land conversion into oil palm plantations is happening with little or no monitoring on the part of those government agencies (e.g. Palawan Council for Sustainable Development) that are responsible for the sustainable management of the Province.

The new trend in the Philippine Market: switching from coconut to palm oil

There is a new trend in the Philippines, leading to the acceleration of oil palm expansion. National vegetable oil millers and refiners are now keen on selling the cheaper palm oil for the domestic market, so that all coconut oil would be exported. Coconut oil, in fact, commands a higher premium in the international market. However, contrary to oil palms, coconut cultivation is endemic to the Philippines and this palm provides multiple products to local farmers, thus sustaining household based economy.

Since 2005, cooking oil manufacturers have increased imports of the cheap palm oil by 90 percent. The use of the palm oil has progressively increased in the local market as household consumers and institutional buyers have preferred it because of the price difference compared with edible coconut oil. Fast-food giants such as Jollibee Foods Corp., have switched to palm oil for their business.

The General Context of Oil Palm Development

Crude palm oil (CPO) consumption worldwide has doubled between 2000 and 2010 with the main new demand coming from Eastern Europe, India and China. By and large, the price of palm oil has increased almost steadily over the past 20 years. Two countries in South East Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia, produce over 80% of the internationally traded CPO. While significant expansion is occurring in Thailand, Papua New Guinea, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo and it is now taking over in the Philippines. Currently there are an estimated 4 million hectares of land under oil palms in Malaysia and over 7.5 million hectares in Indonesia. In Peninsular Malaysia, the palm oil frontier has come near to the limits of land availability and most expansion within Malaysia is now in the two Eastern States of Sabah and Sarawak. Much of the investment for oil palm expansion has come from European Banks but, increasingly, funds are being raised from Islamic banks in the Middle East, and from investors from India and China. It has been estimated that about two thirds of the companies opening lands to plant oil palm in Indonesia are majority-owned by Malaysian conglomerates

The economies of scale and the characteristics of oil palm favor the development of large plantations, meaning that land needs to be acquired in large blocks and huge areas converted to monocultures. Obviously, this pressure to acquire land has implications for those who currently own the same areas, who are for the most part ‘indigenous peoples’ and small household farmers. Since 2004, international and local NGOs have produced a series of detailed reports based on field surveys and the direct testimony of affected people, which document the serious human rights abuses resulting from the imposition of oil palm plantations. The publications show that these abuses are widespread, are inherent in the way lands are acquired and estates are developed and continue up to the present day. Among the most persistent problems are the following: acquisition of lands and smallholder schemes violates the rights of indigenous peoples to their property. Their lands are being taken off them without due payment and without remedy. In addition, their right to give or withhold their free, prior and informed consent for these proposed developments is being violated. In Indonesia, those that sign up to join imposed schemes are not informed that this reallocation of lands implies a permanent surrender of their rights in land. The dramatic changes in local landscapes and ecosystems - including the loss of agricultural and agroforestry lands, hunting grounds, game, fish, forests, as well as water for drinking, cooking and bathing - in turn have major consequences and deprive people of their customary livelihoods and means of subsistence.

Unfair processes of land use allocation and land acquisition and the lack of respect for local communities and indigenous peoples’ rights not only result in marginalization and impoverishment but also give rise to long term disputes over land, which all too often escalate into conflicts with concomitant human rights abuses due to repressive actions by company or State security forces.

Generally, when large agricultural firms enter an area, community members loose access to traditional food zones and other NTFP resources. As a result, they end up becoming employers of oil palm plantations. Lacking legal title to their land, deals are often structured so that members of the community acquire 2-3 hectares (508 acres) of land for oil palm cultivation. In Borneo (Eastern Malaysia and Kalimantan) they typically borrow some $3,000-6,000 (at 30 percent interest per year) from the parent firm for the seedlings, fertilizers, and other supplies. Because oil palm takes roughly 7 years to bear fruit, they work as day laborers at $2.50 per day on mature plantations. In the meantime their plot generates no income but requires fertilizers and pesticides, which are purchased from the oil palm company. Once their plantation becomes productive, the average income for a 2 hectare allotment is $682-900 per month. In the past, rubber and wood generated $350-1000 month (see Lisa Curran studies and WWF Germany reports).

Loss of Biodiversity

As of now, scientific evidence indicates that beyond the obvious deforestation that results from clearing lowland rainforest for plantations, there is a significant reduction (on the order of 80 percent for plants and 80-90 percent for mammals, birds, and reptiles) in biological diversity following forest conversion to oil palm plantation. Moreover, the use of herbicides and pesticides used in oil palm plantations heavily pollutes local waterways. Notoriously, further destruction of peat land has increases the risk of flooding and fire.

The Legal Framework

The legal frameworks in the world’s two foremost palm oil producing countries are inappropriate to protect indigenous peoples’ rights and ensure an equitable development process. In spite of innovative environmental and pro-indigenous legislation, also in the Philippines the issue of oil palm expansion with reference to farmers and indigenous peoples’ rights does show a high degree of paucity.

International organizations have begun to pin their hopes of reform on the creation of a global market in carbon to curb deforestation, although whether this will help or harm indigenous peoples is a matter of debate. Indeed, initial calculations based on current prices, in the voluntary carbon trading market, suggest that market-based payments for Reducing in Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) will not be enough by themselves to make economies based on maintaining natural forests competitive with oil palm. If, however, there is to be a real moratorium on land clearance then this may provide an important opportunity for the Government to effect reforms in the forestry and plantations sectors, take firm steps to amend the laws so they recognize indigenous peoples’ rights and adopt a more measured approach to rural development that gives priority to local communities’ initiatives and not the interests of foreign backed companies.

In the international arena, civil society is presently engaging with processes of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which is an initiative established by businesses involved in the production, processing and retail of oil palm and WWF. Key members include Malaysian and Indonesian palm oil companies and European processing and retailing companies. RSPO is attempting to agree and apply an industry best practice standard for the production and use of palm oil in socially and environmentally acceptable ways. Civil society engagement in this process has secured: 1) the establishment of the RSPO Task Force on Smallholders, which has Developed Guidance to ensure smallholder engagement; 2) strong social protections and requirements for respect for the rights of indigenous peoples, workers, women in the RSPO Principles and Criteria (the standard); and 3) a certification process that is meant to ensure adherence to the standard.

However, there are major concerns about this process, such as the growing concern that RSPO members are operating to double standards, most indigenous peoples and local communities and smallholders remain unaware of the RSPO and are still unclear how they can use it to secure their rights and fair development outcomes. Wider awareness needs to be fostered among NGOs to build on the gains, if any, being made at the RSPO, among others. To date, sustained civil society engagement with the industry and national dialogues about oil palm have been limited to Indonesia and to a lesser extent Malaysia. In the Philippines, local actions in addressing oil palm issues have so far been limited and thus, there is a need for greater sharing and concerted action at the local/national and regional levels.

* Section of this report have been extracted from Forest People Programme (FPP) report: “Palm oil and indigenous peoples in South East Asia. Land acquisition, human rights violations and indigenous peoples on the palm oil frontier” by Marcus Colchester. Other sources: The Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI), RECOFTC, Sawit Watch, the Samdhana Institute, Dr. Lisa M. Curran, School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale University, WWF Germany.

What you can do:

Sign the online Petition to Stop Mining and Oil Palm Expansion in Palawan

And address your concerns to:

*PALAWAN COUNCIL FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (PCSD)

oed@pcsd.ph . AND c/o Mearl Hilario mearlhilario@yahoo.com

FAX: 0063 (048) 434-4234

*Honorable Governor of Palawan

Baham Mitra

abmitra2001@yahoo.com FAX: 0063 (048) 433-2948

*Palawan Project Manager

Agumil Philippines, Inc

Agusan Plantations Group. Fax 0063 323444884

*Mrs. Gilda E. Pico, President and CEO, Land Bank of the Philippines

landbank@mail.landbank.com Fax: 0063 2 528-8580

or contact the ALDAW Network (Ancestral Land/Domain Watch) aldawnetwork@gmail.com

Source: ALDAW Network

Wednesday, August 04, 2010

PCSD endorsement to Macroasia multi-billion giant deferred: an initial victory for NGOs and indigenous peoples

Puerto Princesa - ALDAW - On July 30, over 20 members of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) - a local government body in charge of the protection and sustainable management of the Province meet to decide whether to issue a SEP (Strategic Environmental Plan) clearance to the mining operations of MacroAsia Corporation (MAC for brevity) with reference to a 91ha area, out of the approved Mineral Production Sharing Agreement area of over 1300 hectares.

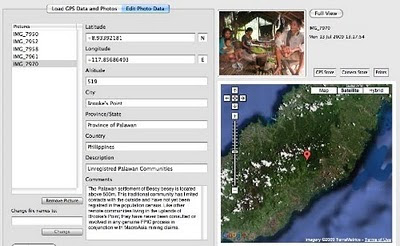

The area for which SEP clearance is being sought consists of well-conserved forest which provides clean water to lowland communities and which is also part of the traditional territory of Palawan tribes living in Brooke’s Point Municipality. During the last PCSD meeting, thanks to the support of Atty Grizelda Mayo-Anda (representing the NGOs community within the Council) and through the effective mediation of Governor Abraham Kahlil Mitra, the ALDAW network (Ancestral Land Domain Watch) was allowed to present ‘geotagged’ findings collected in two separate field surveys carried out in collaboration with the Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) of the University of Kent (UK). In a photographic context, geotagging is the process of associating photos with specific geographic locations using GPS coordinates. GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of a professional device connected to the camera’s hot shoe during the entire mission’s reconnaissance in the hinterlands of Ipilan and Maasin (Brooke’s Point Municipality). The obtained GPS coordinates were later overlaid on PCSD maps to show the overlapping between core zones and MAC mining activities. Overall the findings indicates that: 1) over 95% of test pits and drilling holes in MAC MPSA area are located in “core zones” and biodiversity rich forest, 2) Isolated Indigenous communities are living in the MPSA area of MAC (these have never been consulted about MAC operations); 3) The 91ha for which SEP clearance is being sought by MAC (out of a total MPSA area of more than 1,300 ha) overlap partially with “core zones” and entirely with well-conserved and residual forest. Even more surprisingly, the mission found no evidence of test pits and drilling holes in the recommended 91ha area. “This area includes sacred places where our Palawan indigenous communities carry out their own rituals. Moreover, portions of the Ipilan river and other tributaries which provide potable and irrigation waters to the lowland farmers are also found inside the area” explained ALDAW Chairman Artiso Mandawa.

The area for which SEP clearance is being sought consists of well-conserved forest which provides clean water to lowland communities and which is also part of the traditional territory of Palawan tribes living in Brooke’s Point Municipality. During the last PCSD meeting, thanks to the support of Atty Grizelda Mayo-Anda (representing the NGOs community within the Council) and through the effective mediation of Governor Abraham Kahlil Mitra, the ALDAW network (Ancestral Land Domain Watch) was allowed to present ‘geotagged’ findings collected in two separate field surveys carried out in collaboration with the Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) of the University of Kent (UK). In a photographic context, geotagging is the process of associating photos with specific geographic locations using GPS coordinates. GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of a professional device connected to the camera’s hot shoe during the entire mission’s reconnaissance in the hinterlands of Ipilan and Maasin (Brooke’s Point Municipality). The obtained GPS coordinates were later overlaid on PCSD maps to show the overlapping between core zones and MAC mining activities. Overall the findings indicates that: 1) over 95% of test pits and drilling holes in MAC MPSA area are located in “core zones” and biodiversity rich forest, 2) Isolated Indigenous communities are living in the MPSA area of MAC (these have never been consulted about MAC operations); 3) The 91ha for which SEP clearance is being sought by MAC (out of a total MPSA area of more than 1,300 ha) overlap partially with “core zones” and entirely with well-conserved and residual forest. Even more surprisingly, the mission found no evidence of test pits and drilling holes in the recommended 91ha area. “This area includes sacred places where our Palawan indigenous communities carry out their own rituals. Moreover, portions of the Ipilan river and other tributaries which provide potable and irrigation waters to the lowland farmers are also found inside the area” explained ALDAW Chairman Artiso Mandawa.

The area for which SEP clearance is being sought consists of well-conserved forest which provides clean water to lowland communities and which is also part of the traditional territory of Palawan tribes living in Brooke’s Point Municipality. During the last PCSD meeting, thanks to the support of Atty Grizelda Mayo-Anda (representing the NGOs community within the Council) and through the effective mediation of Governor Abraham Kahlil Mitra, the ALDAW network (Ancestral Land Domain Watch) was allowed to present ‘geotagged’ findings collected in two separate field surveys carried out in collaboration with the Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) of the University of Kent (UK). In a photographic context, geotagging is the process of associating photos with specific geographic locations using GPS coordinates. GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of a professional device connected to the camera’s hot shoe during the entire mission’s reconnaissance in the hinterlands of Ipilan and Maasin (Brooke’s Point Municipality). The obtained GPS coordinates were later overlaid on PCSD maps to show the overlapping between core zones and MAC mining activities. Overall the findings indicates that: 1) over 95% of test pits and drilling holes in MAC MPSA area are located in “core zones” and biodiversity rich forest, 2) Isolated Indigenous communities are living in the MPSA area of MAC (these have never been consulted about MAC operations); 3) The 91ha for which SEP clearance is being sought by MAC (out of a total MPSA area of more than 1,300 ha) overlap partially with “core zones” and entirely with well-conserved and residual forest. Even more surprisingly, the mission found no evidence of test pits and drilling holes in the recommended 91ha area. “This area includes sacred places where our Palawan indigenous communities carry out their own rituals. Moreover, portions of the Ipilan river and other tributaries which provide potable and irrigation waters to the lowland farmers are also found inside the area” explained ALDAW Chairman Artiso Mandawa.

The area for which SEP clearance is being sought consists of well-conserved forest which provides clean water to lowland communities and which is also part of the traditional territory of Palawan tribes living in Brooke’s Point Municipality. During the last PCSD meeting, thanks to the support of Atty Grizelda Mayo-Anda (representing the NGOs community within the Council) and through the effective mediation of Governor Abraham Kahlil Mitra, the ALDAW network (Ancestral Land Domain Watch) was allowed to present ‘geotagged’ findings collected in two separate field surveys carried out in collaboration with the Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) of the University of Kent (UK). In a photographic context, geotagging is the process of associating photos with specific geographic locations using GPS coordinates. GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of a professional device connected to the camera’s hot shoe during the entire mission’s reconnaissance in the hinterlands of Ipilan and Maasin (Brooke’s Point Municipality). The obtained GPS coordinates were later overlaid on PCSD maps to show the overlapping between core zones and MAC mining activities. Overall the findings indicates that: 1) over 95% of test pits and drilling holes in MAC MPSA area are located in “core zones” and biodiversity rich forest, 2) Isolated Indigenous communities are living in the MPSA area of MAC (these have never been consulted about MAC operations); 3) The 91ha for which SEP clearance is being sought by MAC (out of a total MPSA area of more than 1,300 ha) overlap partially with “core zones” and entirely with well-conserved and residual forest. Even more surprisingly, the mission found no evidence of test pits and drilling holes in the recommended 91ha area. “This area includes sacred places where our Palawan indigenous communities carry out their own rituals. Moreover, portions of the Ipilan river and other tributaries which provide potable and irrigation waters to the lowland farmers are also found inside the area” explained ALDAW Chairman Artiso Mandawa. In a nutshell the joint ALDAW/CBCD presentation clearly demonstrates that MAC mining interests are really concentrated in primary virgin forest. Geotagged photos portray test pits and drilling holes, found around 800m and even above 1,000m ASL. These evidences generated a lively debate amongst PCSD council members. PCSD representative/Congressman Antonio C. Alvarez asked confirmation to MacroAsia spokesman on whether their explorations activities are really located in core zones of “maximum protection”. To the surprise of all participants, MACROASIA representatives did not deny but rather confirmed the evidences brought forward by the ALDAW investigation team. However, they also stated that their permit to explore in ‘core zone’ was legally given by DENR and further endorsed through a SEP clearance by the PCSD. This assertion gave more ground to Congressman Alvarez to challenge Romeo Dorado, PCSD executive director: “a permit to explore core zones is not just a piece of paper, it actually entails the manipulation and disturbance of areas that, in principle, should be maintained free of human disruption. If the PCSD has allowed the exploration of core zones, it means that there is something wrong here” said Alvarez. Director Romeo Dorado clarified that, although the area used by MAC for exploration purposes is mostly located in core zones, the PCSD is only prepared to endorse to MacroAsia 91ha area out of the total MAC MPSA area of about 1300ha. Dorado’s reassurance was unconvincing and raised more questions than answers. In fact, according to the evidence presented by ALDAW team, there are no signs of exploration in the proposed 91hectares, no test pits and drilling holes and – in fact – as it was later confirmed by MacroAsia itself - no valuable minerals are found in the applied area. “What’s the purpose of getting an endorsement for this area, while the minerals that the companies want to extract are located much further in the uplands?” asked Alvarez. Atty Gerthie Mayo-Anda picked up on this argument: “we should really understand the ‘economic implications’ of the 91-hectare area. Surely if the company does not consider it commercially viable to just mine 91 hectares, they would want a much larger area which means that their targets for mineral extraction are really the core zones and the protected area!” said Mayo-Anda. Again, MacroAsia representatives had no valid argument on which to cling and rather admitted that the 91ha area for which SEP clearance is requested will be used as an ‘installation base for the company’. Having said this, MAC representatives provided no information on the exact location where the actual mining extraction would actually take place. During the meeting, Atty. Mayo-Anda further stressed that MAC’s MPSA area is located inside the recently declared Mount Mantalingahan Protected Landscape (MMPL), pursuant to Presidential Proclamation no. 1815. MacroaAsia representatives contested the assertion by claiming that, according to the same Proclamation, any valid contract for the extraction of natural resources already existing prior to the proclamation should be respected until its expiration. According to Dr. Dario Novellino (CBCD researcher and partner of ALDAW) the MAC spokesmen omitted a very important paragraph found in the same proclamation which specifies that areas covered by such contracts, which are found not viable for development after assessment shall automatically form part of the MMPL. “According to our field research, the areas claimed by MAC is not viable for any form of aggressive development, due to its particular ecological characteristics and specific landscape value” said Novellino. Atty. Mayo-Anda further challenged the MAC spokesman by clarifying that “the vested argument is skewed and cannot be sustained. It is well-settled in Philippine jurisprudence that exploration, development and utilization of natural resources through licenses, concessions or leases are mere grants or privileges by the State; and being so, they may be revoked, rescinded, altered or modified when public interest so requires” said Mayo-Anda. While MacroAsia representatives admitted that their concession overlaps with the Mantalinghan Proclaimed area, they also questioned how much of it is really located in core zones. “Part of their defence argument was based on their own subjective interpretation of core zone. They kept arguing that ‘core zones’ are above 1000 m ASL, to prove that most of their exploration and extractive activities are legal, being below that altitude. In reality according to SEP law core zones do not just include areas above 1000 meters elevation but all types of natural forest: first growth forest, residual forest and edges of intact forest, endangered habitats, etc. These are exactly the kind of places where MAC has been concentrating its own mining activities” said Novellino.

To the surprise of both NGOs and indigenous participants, the representative of the Mineral Geoscience Bureau of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources proposed that it would be better to revise the ‘core zones’ rather than challenging the company’s actions and operations. Again this statement ignited the debate even further “ECAN amendment in Brooke’s Point would be inconsistent. Any proposed change to the zoning system should be discussed publically in a Barangay Assembly and in close consultation with the communities. Core zones should be protected rather than amended to accommodate the interests on the mining companies” responded Mayo-Anda and Congressman Alvarez.

In addition to geotagging and ocular inspection, MacroAsia was also challenged on the bases of social acceptability. “It will not be difficult to establish that the people of Brookes Point are overwhelmingly against any mining. This is what we indigenous peoples and farmers have been trying to communicate to the government for the past two years through public demonstrations and rallies but they did not listen” said ALDAW Chairman Artiso Mandawa.

MAC representatives insisted that, as far as social acceptability is concerned, all documentation from the National Council for Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) had already been secured. However, according to Commissioner Atty. Felongco representing the NCIP on the meeting “applications are still pending and no final decision by NCIP has been made. On the contrary, we have been requesting additional documentation to the local government, since two barangays have not yet been consulted”. Governor Baham, chairing the meeting, expressed his discontentment for the NCIP inability to respond promptly to the lack of documentation relating to ‘social acceptability’. “From now on, NCIP provincial office should communicate its findings directly to the NCIP national office. Passing through the regional office, delays the whole procedures and creates anomalies” said Governor B. Mitra. He also posed the question on whether and to what extent previous local government endorsements to MacroAsia would still be confirmed after the forthcoming Barangay election. “I think all these crucial matters should be re-discussed and reviewed by the new barangay administration, as soon as it is elected and become operative” said Governor Mitra. Adding more points to the argument, Atty. Mayo-Anda suggested “municipal government officials should visit personally the area claimed by MAC to get a clear idea of the location, vegetation cover and actual land uses; and such crucial decision cannot be made just by tracing lines on a map”. During the PCSD meeting, also former Congressman Alfredo Amor Abueg Jr. asked the Council for a re-evaluation of all requirements provided by MacroAsia, especially those related to Barangay government, NCIP and to the Province itself. “All previous endorsements given by the local government should now be re-evaluated on the bases of evidences brought forward by the ALDAW team” he said.

Hon. Baham Mitra, Governor of Palawan and newly elected PCSD chairman, finally approved the motion. This entails that the decision to endorse a SEP clearance to MacroAsia is deferred until a multipartite team composed of PCSD technical staff, local government officials, NGOs and Indigenous Peoples’ representatives visits the proposed area and investigates the ALDAW findings and all pending issues raised by the NGO community. The team should also be in charge of determining: 1) the legality of endorsements by local government units; 2) the expected impact of mining on indigenous culture and livelihood; 3) the potential impact of mining on tourism industry; 4) the economic value of the 91 hectares for which SEP clearance is being sought by MacroAsia.

“This is just an initial victory for the indigenous peoples and our NGOs supporters” commented Artiso Mandawa (ALDAW Chairman) at the end of the meeting. “It proves that illicit affairs are not unstoppable, when the evidence brought forward is there to light up every dark corner and to expose all bed practices of mining companies and their political allies” addend Mandawa.

Some reflections on the way forward

The last PSCD meeting agenda has shed light on a number of issues that apply not only to MacroaAsia but to the vast majority of mining companies in Palawan whose operations can be questioned both from the perspective of ‘social acceptability’ and ‘environmental sustainability’. Several major mining projects that are in the pipeline in Palawan have been endorsed by local government officials, but have not been approved by the communties that would host them. Mining incursion in core zones and forested areas of high-biological diversity has already occurred in other areas. Geotagging findings, as those collected with reference to MacroAsia MPSA area, have already been gathered for the concession areas of Ipilan Nickel Corporation (INC) bordering MAC concession, as well as for Bulanjao range, one of the most valuable biodiversity hot spots in Southern Palawan. Here the mining road of Rio-Tuba Nickel Mining Corporation has already reached the highest fringes of the Bulanjao, at an latitude of 859m, causing deforestation, sever soil erosion and damage to the Sumbiling river watersheds. Evidence indicates that also the mining applications of Narra Nickel Mining and Development, Inc. (NNMDC), Tesoro Mining and Development, Inc. (TMDI), and McArthur Mining, Inc. (MMI) - approved through a Financial and Technical Assistance Agreement (FTAA) – and partnering with the Canadian MBMI - will surely encroach into core zones leading to the devastation of precious watersheds, indigenous ancestral territories and productive rice-land. The same applies to the City Nickel company in Espanola municipality and Fujian-Sino Mining Corp in Roax Municipality.

To avoid the transformation of Palawan (the Last Philippine’s Frontier) into a mining destination the following actions would be required.

The Local Government (LGU)

The LGU should ensure that all mining related decisions which are likely to affect local communities and their environment, be discussed with an independent committee formed by indigenous peoples, local farmers, NGOs and IPs organizations’ representatives in order to enhance transparency and accountability in decision making process.

Moreover, the LGUs should stick to their original Municipal Comprehensive Land Use Plans (CLUPs) without trying to reclassify ECAN zones into multiple/manipulative use zones to allow extractive activities.

The PCSD should stop issuing permits to mining companies to operate in ecologically precious and/or fragile areas, since this is in violation with the agency’s own mandate. Even more importantly, PCSD should stop any attempt of changing the definition of core zones and other zones to allow mining activities in forested land. It has already been established that some definitions such as those of ‘controlled use zones’ have been amended by the Council to please big corporations’ interests. For instance, according to the SEP law, in Controlled Use Area – (the outer protective barrier that encircles the core and restricted use areas) “strictly controlled mining and logging, which is not for profit…may be allowed”. Recently the ‘not for profit’ specification has been eliminated, thus opening these zones to commercial extractive activities.

Evidence, also indicate that PCSD maps are also inconsistent with the SEP zoning criteria. For instance, those areas that encircle and provide a protective buffer to the ‘core zones’, rather than being demarcated in blue (the color of restricted-use zones) are demarcated in brown, the color of ‘controlled use zones’ where mining is now allowed. These inconsistencies should be explained and rectified by the PCSD, as soon as possible.

Before, issuing SEP clearances the PCSD should consult indigenous and farmers communities. As of now, this has never been the case.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)

The DENR should stop fast-tracking mining contracts in Palawan. It should make watersheds off-limits to mining, as well as those areas of high biodiversity and endemism, to include Indigenous Peoples’ Ancestral Domains. This should lead to the suspension of all existing MPSA and FTAA until all controversial issues and ambiguities are clarified.

Ultimately, the DENR should solve its inherent conflict of interest caused by its dual functions: on one hand protecting the environment and the indigenous peoples and, on the other, promoting mining. Therefore, it is suggested that the responsibility related to the issuing of mining licenses should be dealt with by the Department of Mines, Hydrocarbons and Geosciences.

The NCIP

NCIP should stop issuing certificate of pre condition/clearances to mining applications and influencing indigenous peoples into endorsing mining projects. NCIP should also ensure that all FPIC processes carried out in conjunction with mining issues are evaluated by an independent body formed by indigenous leaders elected by their own communities, by representatives of indigenous organizations and, if the latter require so, by members (researchers, journalists, advocates, etc) of foreign institutions.

The National Government

The State should call for an immediate halt of mining operations in Palawan since such activities contravene those provisions contained in well-know conventions ratified by the Philippine Gove[e.g. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)], the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage and; the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Ultimately, the National Government should revoke the 1995 mining act and issue a new act placing more emphasis on human rights and ecological balance, while regulating mining for the public interest.

The Provincial Government

In late 2008, the provincial board of Palawan has passed a provincial resolution providing for a moratorium on small-scale mining for a period of 25 years. This local legislative effort is not enough to prevent large scale and exploration activities in the province. The Provincial Government should prove and demonstrate to the National Government that the revitalization of the mining industry is not compatible with the special environmental status of Palawan Island, nor with the PCSD’s primary goal of achieving sustainable development in accordance with the Strategic Environmental Plan (RA 7611).

The UNESCO

Having established Palawan as a “Man and Biosphere Reserve” the UNESCO should play a more incisive and pro-active role, specifically when national governments, such as the Philippines, violate the condition for which such ‘prestigious awards’ have been granted.

Source: ALDAW

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Counter-mapping in the Philippines: The Gantong Geo-Tagged Report

On July 2009, a mission led by the Philippine-based Ancestral Land/Domain Watch (ALDAW) and the Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) at the University of Kent traveled to the eastern side of the Gantong range, in Brooke’s Point Municipality, Province of Palawan. Palawan is part of the “Man and Biosphere Reserve” program of UNESCO and hosts 49 animals and 56 botanical species found in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

The mission’s actual ‘matching’ of collected GPS data to photographs shows that the Mineral Production Sharing Agreements (MPSA) of two mining firms [MacroAsia and Celestial Nickel Mining and Exploration Corporation (CNMEC) now operated by Ipilan Nickel Corporation (INC)] overlap with precious watersheds endowed with numerous creeks, springs and waterfalls providing potable water to the local indigenous communities and lowland farmers. More importantly, under the ECAN Guidelines of the Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan (Republic Act 7611), such areas constitute the so called “core zones” of maximum protection where industrial extractive activities are not allowed.

The mission’s actual ‘matching’ of collected GPS data to photographs shows that the Mineral Production Sharing Agreements (MPSA) of two mining firms [MacroAsia and Celestial Nickel Mining and Exploration Corporation (CNMEC) now operated by Ipilan Nickel Corporation (INC)] overlap with precious watersheds endowed with numerous creeks, springs and waterfalls providing potable water to the local indigenous communities and lowland farmers. More importantly, under the ECAN Guidelines of the Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan (Republic Act 7611), such areas constitute the so called “core zones” of maximum protection where industrial extractive activities are not allowed.

At an altitude of about 500m ASL the mission reached indigenous settlements inhabited by very traditional Palawan having limited contacts with the outside. Their sustenance totally depends on the available forest resources, and it consists of a heterogeneous economy where sustainable swidden cultivation is integrated with foraging and the collection of non-timber forest products (NTFPs).

Overall, the mission moved from an elevation of a few meters ASL to an altitude of about 670m ASL, where one of the furthermost Palawan settlements is located. The mission’s GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of the JOBO GPS device being connected to the camera’s hot shoe. Positions were taken at intervals of several meters in order to reconstruct the mission’s full itinerary. The geo-tagged images were then loaded into ‘Photo GPS Editor’ and displayed on satellite Google map. All upland Palawan interviewed during the ALDAW/CBCD mission have declared that they have never been consulted about the entrance of mining companies in their traditional territories.

According to indigenous representatives, the Palawan branch of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) – the government body mandated to ‘protect and promote the interest and well-being of cultural communities’ – is now siding with the mining companies. It is hoped that the ALDAW/CBCD Gantong geo-tagged report will facilitate the circulation of information, at both the national and international levels, on the threats faced by ‘irresponsible mining’ in the Philippines’ “last frontier”. An international campaign to support indigenous Palawan claims to their ancestral land has also been initiated by Survival International.

Source: The ALDAW NETWORK

The ALDAW NETWORK (Ancestral Land/Domain Watch) is an advocacy-campaign network of Indigenous Peoples jointly constituted by NATRIPAL (United Tribes of Palawan) and BANGSA PALAWAN PHILIPPINES (Indigenous Alliance for Equity and Wellbeing) on August 2009.

The mission’s actual ‘matching’ of collected GPS data to photographs shows that the Mineral Production Sharing Agreements (MPSA) of two mining firms [MacroAsia and Celestial Nickel Mining and Exploration Corporation (CNMEC) now operated by Ipilan Nickel Corporation (INC)] overlap with precious watersheds endowed with numerous creeks, springs and waterfalls providing potable water to the local indigenous communities and lowland farmers. More importantly, under the ECAN Guidelines of the Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan (Republic Act 7611), such areas constitute the so called “core zones” of maximum protection where industrial extractive activities are not allowed.

The mission’s actual ‘matching’ of collected GPS data to photographs shows that the Mineral Production Sharing Agreements (MPSA) of two mining firms [MacroAsia and Celestial Nickel Mining and Exploration Corporation (CNMEC) now operated by Ipilan Nickel Corporation (INC)] overlap with precious watersheds endowed with numerous creeks, springs and waterfalls providing potable water to the local indigenous communities and lowland farmers. More importantly, under the ECAN Guidelines of the Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan (Republic Act 7611), such areas constitute the so called “core zones” of maximum protection where industrial extractive activities are not allowed.At an altitude of about 500m ASL the mission reached indigenous settlements inhabited by very traditional Palawan having limited contacts with the outside. Their sustenance totally depends on the available forest resources, and it consists of a heterogeneous economy where sustainable swidden cultivation is integrated with foraging and the collection of non-timber forest products (NTFPs).

Overall, the mission moved from an elevation of a few meters ASL to an altitude of about 670m ASL, where one of the furthermost Palawan settlements is located. The mission’s GPS coordinates were obtained through the use of the JOBO GPS device being connected to the camera’s hot shoe. Positions were taken at intervals of several meters in order to reconstruct the mission’s full itinerary. The geo-tagged images were then loaded into ‘Photo GPS Editor’ and displayed on satellite Google map. All upland Palawan interviewed during the ALDAW/CBCD mission have declared that they have never been consulted about the entrance of mining companies in their traditional territories.

According to indigenous representatives, the Palawan branch of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) – the government body mandated to ‘protect and promote the interest and well-being of cultural communities’ – is now siding with the mining companies. It is hoped that the ALDAW/CBCD Gantong geo-tagged report will facilitate the circulation of information, at both the national and international levels, on the threats faced by ‘irresponsible mining’ in the Philippines’ “last frontier”. An international campaign to support indigenous Palawan claims to their ancestral land has also been initiated by Survival International.

Source: The ALDAW NETWORK

The ALDAW NETWORK (Ancestral Land/Domain Watch) is an advocacy-campaign network of Indigenous Peoples jointly constituted by NATRIPAL (United Tribes of Palawan) and BANGSA PALAWAN PHILIPPINES (Indigenous Alliance for Equity and Wellbeing) on August 2009.

Friday, September 18, 2009

Applications of GIS in Community Forestry: Linking Geographic Information Technology to Community Participation

Planning and managing forest resources in todays ever-changing world is becoming very complex and demanding challenges to forest resource managers. Because of the multiple interests of forest users and other community interest groups, a wider range of up-to-date information is being requested in community forestry, than has been used in conventional government-based forest management in the past. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and related technologies provide foresters and resource planners with powerful tools for planning, management and decision making. Recent trend towards community based forest management has added new dimensions and potential to use of GIS in community forestry. This book explores the potential and constraints for the application of GIS technology in community based forestry. This book will be of interest to forest managers, community development practitioners, researchers and students interested in using GIS technology in forestry and participatory GIS.

Saturday, June 20, 2009

Map symbols and coding means

Map symbols should be designed or chosen according to principles of logic and communication to serve as a graphic code for storing and retrieving data in a two or three dimensional geographic framework.

Appreciating the logic of map symbols begins with understanding the existence of three distinct categories, including point, line and polygons (areas).

Maps and 3D models include generally a combination of all three. These tree main categories can be further differentiated by variations in "hue" (color), "gray tone value", "texture" and "orientation", "shape" and "size".

Each of these variables or their combinations excel in portraying particular features and their variations.

When using color (hue) for characterizing areas, decoding is made simpler when darker means "more" and lighter means "less". Color conventions allow map symbols to exploit idealized associations of water with blue and forested areas with green. This the combination of the two, implies that dense primary forest is dark green, secondary forest green, and grassland light green, and that deep waters are dark blue and shallow waters light blue .

"Size" is more suited to for showing different in amount of count, whereas "variations in gray tone" are preferred for distinguishing differences in rate or intensity. Symbols varying in orientation are useful mostly for representing directional occurrences like winds, migration streams or other. Line symbols best portray water courses, roads, trails, boundaries and may combine different variables, including color and size (thickness). A heavier line readily suggests greater capacity or heavier traffic than a thin line implies.

Each symbol should be easily discernable from all others to clearly distinguish unlike features and provide a sense of graphic hierarchy. A poor match between the data and the visual variables may frustrate and confuse the map user.

While in planimetric mapmaking the only limitation in the choice of symbols is fantasy (with logic), participatory 3-D modeling (P3DM) frequently depends on the availability of materials, particularly for point features which are generally represented by push and map pins. Lines and polygons can be easily represented by color-coded yarns and different color paints.

Standardization of symbols serves for ready unambiguous recognition of features and promotes efficiency in both map production and use, exchange of data and comparison. Maps and models sharing a common graphic vocabulary are definitely more powerful in convening the intended message and decoding simpler.

Appreciating the logic of map symbols begins with understanding the existence of three distinct categories, including point, line and polygons (areas).

Maps and 3D models include generally a combination of all three. These tree main categories can be further differentiated by variations in "hue" (color), "gray tone value", "texture" and "orientation", "shape" and "size".

Each of these variables or their combinations excel in portraying particular features and their variations.

When using color (hue) for characterizing areas, decoding is made simpler when darker means "more" and lighter means "less". Color conventions allow map symbols to exploit idealized associations of water with blue and forested areas with green. This the combination of the two, implies that dense primary forest is dark green, secondary forest green, and grassland light green, and that deep waters are dark blue and shallow waters light blue .

"Size" is more suited to for showing different in amount of count, whereas "variations in gray tone" are preferred for distinguishing differences in rate or intensity. Symbols varying in orientation are useful mostly for representing directional occurrences like winds, migration streams or other. Line symbols best portray water courses, roads, trails, boundaries and may combine different variables, including color and size (thickness). A heavier line readily suggests greater capacity or heavier traffic than a thin line implies.

Each symbol should be easily discernable from all others to clearly distinguish unlike features and provide a sense of graphic hierarchy. A poor match between the data and the visual variables may frustrate and confuse the map user.

While in planimetric mapmaking the only limitation in the choice of symbols is fantasy (with logic), participatory 3-D modeling (P3DM) frequently depends on the availability of materials, particularly for point features which are generally represented by push and map pins. Lines and polygons can be easily represented by color-coded yarns and different color paints.

Standardization of symbols serves for ready unambiguous recognition of features and promotes efficiency in both map production and use, exchange of data and comparison. Maps and models sharing a common graphic vocabulary are definitely more powerful in convening the intended message and decoding simpler.

Labels:

coding,

flagpins,

geo,

geocoding,

geotagging,

indigenous mapping,

map pins,

neogeography,

p3dm,

pgis,

pins,

ppgis,

pushpins,

symbols

Sunday, January 18, 2009

Geotagging Picasa photos in Google Earth

This video describes how to geotag Picasa photos in Google Earth.

Monday, January 05, 2009

Photo Geotagging & GPS Photo Trackers

Geotagging photographs has become an increasingly important aspect of PGIS / PPGIS practice. While the Internet already offers a wide range of online applications (Google Earth, Panoramio, Flikr, etc) where to geo-locate images, offline solutions (hardware & software) are still to be made available or even known to the many of us. I have compiled some data based on an online research dividing the available devices in three groups: Group one includes GPS-enabled cameras. Group 2 includes devices which have to be directly connected to the camera. The third group includes devices which operates separately from the camera and harvest data which have to be matched with the images taken through a three-steps process.

All result in adding latitude, longitude, altitude and time data to photographs taken with digital cameras.

More information on the research is found here.

Labels:

geocoding,

geotagging,

images,

pgis,

photo,

photographs,

ppgis

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)