In 2005, the CPA also created the Abyei Arbitration Tribunal (AAT) which issued a Final and Binding Ruling on the north-south border – which could become an international border following a referendum on Southern Sudan independence slated for 2011.

Kharthoum rejected this Ruling, causing a stalemate until May 2008 when the town of Abyei, ancestral centre for the Ngok Dinka, was methodically sacked by a combination of Misseriya militias and troops from Khartoum - displacing 60,000 residents as collateral.

The border delineated by the AAT had been based on exhaustive interviews with elders from the nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms, coupled with equally exhaustive historical map research. But, none of the sites mentioned by the elders, as evidence of ancestral occupancy, had been geocoded with GPS. The purpose of this mapping project was to rectify that with a repeat performance using GPS.

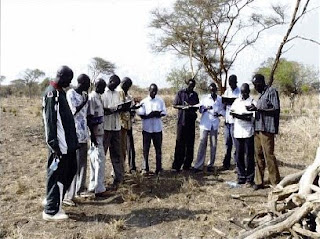

A legal team, from the US-based Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG) and London-based WilmerHale, along with Southern Sudanese, colleagues re-interviewed the elders during a week long conference of all nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms to plan the restoration of Abyei. During that same week, a team of 12 Ngok Dinka were trained in the use GPS units, videos and still cameras. At the same time, the lawyers’ interviews provided the information about the significant historical sites needed by the team to build up a legend. For litigational reasons beyond my understanding it was essential to demonstrate that, by 1905, Ngok Dinka had occupied an area well to the north of Abyei town.

A legal team, from the US-based Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG) and London-based WilmerHale, along with Southern Sudanese, colleagues re-interviewed the elders during a week long conference of all nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms to plan the restoration of Abyei. During that same week, a team of 12 Ngok Dinka were trained in the use GPS units, videos and still cameras. At the same time, the lawyers’ interviews provided the information about the significant historical sites needed by the team to build up a legend. For litigational reasons beyond my understanding it was essential to demonstrate that, by 1905, Ngok Dinka had occupied an area well to the north of Abyei town.Ngok Dinka memory stretched far further back than 1905. A principle signifier of historical occupancy were sites identified with Names for Age Sets, which were changed every ten years. The elders recited age set names and places going back centuries, the oldest stretched to 1508.

The mapping method was simple. Following the Abyei restoration conference, the team visited each chiefdom in turn and spent a day talking with 25 elders, going over recorded sites and seeking more. They then divided into three units and three vehicles, and selected elders guided them to the sites that had been listed. In two stints over the last winter, the mapping team, covered the disputed area and recorded almost 300 sites. Each evening the mapping log book were written up and emailed to International Mapping, Baltimore, US.

With the critical area covered, it was decided that, for the few days remaining the mapping teams, elders, and lawyers, would travel further north – to sites identified by the elders but outside the area that was critical for the Southern Sudan-Ngok Dinka case.

This brought the project to the attention of officials representing Northern Sudan. They were not too happy about it but all the required data was by then at the cartographers in Baltimore. The last few days were spent either under military escort, or waiting for an escort to materialize, or waiting for it to finish eating somewhere. Three trips were eventually made. To varying degrees they were high on inter-group tension but low on data utility so these data do not appear on the around Abyei. Shortly after, there were rumours of a Kharthoum-driven counter mapping effort, but it was too late.

With only a week of training and field exercises under their belts, the Ngok Dinka mapping team did outstanding work. During the recent Abyei Arbitration Tribunal hearing, lawyers for Kharthoum made a serious effort to dismiss their maps as “tainted data” but in the final exchange, they were outplayed by the legal team for Southern Sudan. For anyone seeking field workers in Southern Sudan, there are now several trained and contactable, but jobless, community information gathering and mapping people in circulation in the Abyei area. The

Verdict will be on this site on Wednesday. http://www.pca-cpa.org/ For a good, detailed account of the Abyei issue visit the Enough Project.

Read also: Dr. Peter Poole 2009. Ngok Dinka Abyei Area Community Mapping Project report, February 2009

Peter Poole, 21 July 2009

An Atlas of Radical Cartography

An Atlas of Radical Cartography