Friday, September 18, 2009

Applications of GIS in Community Forestry: Linking Geographic Information Technology to Community Participation

Wednesday, September 16, 2009

How to create a "My Map" in Google Maps

How to create personalized, annotated, customized maps using Google Maps.

Here is an example: P3DM Where?

Head teacher Julius Sangogo reports on the usefullness of a Participatory 3D Model (P3DM) in Nessuit, Kenya

Head teacher Julius Sangogo reports on the usefullness of a Participatory 3D Model in Nessuit, Kenya from CTA on Vimeo.

Three years after the completion of a Participatory 3D model in Nessuit Kenya, head teacher Julius Sangogo recalls the uses of the model by local, national and international agencies and more importantly by the pupils of the local primary school.

The Mystery of Capital among the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon

Part 1 The Mystery of Capital among the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon from ILD on Vimeo.

A film directed by James Becket

Conceived of and written by Hernando de Soto

Produced by Bernardo Roca Rey and Hernando de Soto

Research Director Ana Lucía Camaiora

A Becket Films LLC and Institute for Liberty and Democracy Production

Part 2 The Mystery of Capital among the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon from ILD on Vimeo.

A film directed by James Becket Conceived of and written by Hernando de Soto Produced by Bernardo Roca Rey and Hernando de Soto Research Director Ana Lucía Camaiora A Becket Films LLC and Institute for Liberty and Democracy Production

Part 3 The Mystery of Capital among the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon from ILD on Vimeo.

A film directed by James Becket Conceived of and written by Hernando de Soto Produced by Bernardo Roca Rey and Hernando de Soto Research Director Ana Lucía Camaiora A Becket Films LLC and Institute for Liberty and Democracy Production

Wednesday, September 09, 2009

Participatory 3D Model (P3DM) of Chivoko village, Solomon Islands

Tuesday, September 01, 2009

Qualitative GIS: A Mixed Methods Approach

Geographic Information Systems are an essential tool for analyzing and representing quantitative spatial data. Qualitative GIS explains the recent integration of qualitative research with Geographical Information Systems

With a detailed contextualising introduction, the text is organised in three sections:

Representation: examines how researchers are using GIS to create new types of representations; working with spatial data, maps, and othervisualizations to incorporate multiple meanings and to provide texture and context. This section includes a chapter by Jon Corbett and Giacomo Rambaldi dealing with participatory mapping by the title: "Geographic information technologies, local knowledge, and change (pages 75-91).

Analysis: discusses the new techniques of analysis that are emerging at the margins between qualitative research and GIS, this in the wider context of a critical review of mixed-methods in geographical research

Theory: questions how knowledge is produced, showing how ideas of 'science' and 'truth' inform research, and demonstrates how qualitative GIS can be used to interrogate discussions of power, community, and social action

Making reference to representation, analysis, and theory throughout, the text shows how to frame questions, collect data, analyze results, and represent findings in a truly integrated way. An important addition to the mixed methods literature, Qualitative GIS will be the standard reference for upper-level students and researchers using qualitative methods and Geographic Information Systems.

Available from Amazon.com (US) and Amazon.co.uk (Europe)

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

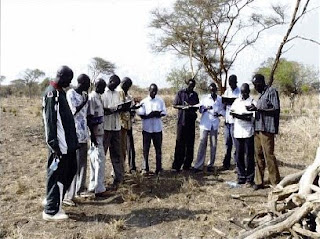

Discrete Community Mapping in Sudan

In 2005, the CPA also created the Abyei Arbitration Tribunal (AAT) which issued a Final and Binding Ruling on the north-south border – which could become an international border following a referendum on Southern Sudan independence slated for 2011.

Kharthoum rejected this Ruling, causing a stalemate until May 2008 when the town of Abyei, ancestral centre for the Ngok Dinka, was methodically sacked by a combination of Misseriya militias and troops from Khartoum - displacing 60,000 residents as collateral.

The border delineated by the AAT had been based on exhaustive interviews with elders from the nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms, coupled with equally exhaustive historical map research. But, none of the sites mentioned by the elders, as evidence of ancestral occupancy, had been geocoded with GPS. The purpose of this mapping project was to rectify that with a repeat performance using GPS.

A legal team, from the US-based Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG) and London-based WilmerHale, along with Southern Sudanese, colleagues re-interviewed the elders during a week long conference of all nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms to plan the restoration of Abyei. During that same week, a team of 12 Ngok Dinka were trained in the use GPS units, videos and still cameras. At the same time, the lawyers’ interviews provided the information about the significant historical sites needed by the team to build up a legend. For litigational reasons beyond my understanding it was essential to demonstrate that, by 1905, Ngok Dinka had occupied an area well to the north of Abyei town.

A legal team, from the US-based Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG) and London-based WilmerHale, along with Southern Sudanese, colleagues re-interviewed the elders during a week long conference of all nine Ngok Dinka chiefdoms to plan the restoration of Abyei. During that same week, a team of 12 Ngok Dinka were trained in the use GPS units, videos and still cameras. At the same time, the lawyers’ interviews provided the information about the significant historical sites needed by the team to build up a legend. For litigational reasons beyond my understanding it was essential to demonstrate that, by 1905, Ngok Dinka had occupied an area well to the north of Abyei town.Ngok Dinka memory stretched far further back than 1905. A principle signifier of historical occupancy were sites identified with Names for Age Sets, which were changed every ten years. The elders recited age set names and places going back centuries, the oldest stretched to 1508.

The mapping method was simple. Following the Abyei restoration conference, the team visited each chiefdom in turn and spent a day talking with 25 elders, going over recorded sites and seeking more. They then divided into three units and three vehicles, and selected elders guided them to the sites that had been listed. In two stints over the last winter, the mapping team, covered the disputed area and recorded almost 300 sites. Each evening the mapping log book were written up and emailed to International Mapping, Baltimore, US.

With the critical area covered, it was decided that, for the few days remaining the mapping teams, elders, and lawyers, would travel further north – to sites identified by the elders but outside the area that was critical for the Southern Sudan-Ngok Dinka case.

This brought the project to the attention of officials representing Northern Sudan. They were not too happy about it but all the required data was by then at the cartographers in Baltimore. The last few days were spent either under military escort, or waiting for an escort to materialize, or waiting for it to finish eating somewhere. Three trips were eventually made. To varying degrees they were high on inter-group tension but low on data utility so these data do not appear on the around Abyei. Shortly after, there were rumours of a Kharthoum-driven counter mapping effort, but it was too late.

With only a week of training and field exercises under their belts, the Ngok Dinka mapping team did outstanding work. During the recent Abyei Arbitration Tribunal hearing, lawyers for Kharthoum made a serious effort to dismiss their maps as “tainted data” but in the final exchange, they were outplayed by the legal team for Southern Sudan. For anyone seeking field workers in Southern Sudan, there are now several trained and contactable, but jobless, community information gathering and mapping people in circulation in the Abyei area. The

Verdict will be on this site on Wednesday. http://www.pca-cpa.org/ For a good, detailed account of the Abyei issue visit the Enough Project.

Read also: Dr. Peter Poole 2009. Ngok Dinka Abyei Area Community Mapping Project report, February 2009

Peter Poole, 21 July 2009

Saturday, June 20, 2009

Map symbols and coding means

Appreciating the logic of map symbols begins with understanding the existence of three distinct categories, including point, line and polygons (areas).

Maps and 3D models include generally a combination of all three. These tree main categories can be further differentiated by variations in "hue" (color), "gray tone value", "texture" and "orientation", "shape" and "size".

Each of these variables or their combinations excel in portraying particular features and their variations.

When using color (hue) for characterizing areas, decoding is made simpler when darker means "more" and lighter means "less". Color conventions allow map symbols to exploit idealized associations of water with blue and forested areas with green. This the combination of the two, implies that dense primary forest is dark green, secondary forest green, and grassland light green, and that deep waters are dark blue and shallow waters light blue .

"Size" is more suited to for showing different in amount of count, whereas "variations in gray tone" are preferred for distinguishing differences in rate or intensity. Symbols varying in orientation are useful mostly for representing directional occurrences like winds, migration streams or other. Line symbols best portray water courses, roads, trails, boundaries and may combine different variables, including color and size (thickness). A heavier line readily suggests greater capacity or heavier traffic than a thin line implies.

Each symbol should be easily discernable from all others to clearly distinguish unlike features and provide a sense of graphic hierarchy. A poor match between the data and the visual variables may frustrate and confuse the map user.

While in planimetric mapmaking the only limitation in the choice of symbols is fantasy (with logic), participatory 3-D modeling (P3DM) frequently depends on the availability of materials, particularly for point features which are generally represented by push and map pins. Lines and polygons can be easily represented by color-coded yarns and different color paints.

Standardization of symbols serves for ready unambiguous recognition of features and promotes efficiency in both map production and use, exchange of data and comparison. Maps and models sharing a common graphic vocabulary are definitely more powerful in convening the intended message and decoding simpler.

Wednesday, June 17, 2009

P3DM after the 2007 World Summit Award

Since 2005 (year in which the project in Fiji was implemented) Participatory 3D Modelling (P3DM) and been adopted in development contexts in many parts of the world (http://www.p3dm.org/) including Cambodia, Colombia, East Timor, Ethiopia, France, Guyana, Italy, Kenya, Malaysia, Nepal, PNG, Australia and other countries.

The 2007 WSA recognition added value and authority to the method and gave worldwide recognition to its quality and appropriateness.

In Kenya P3DM been used by Ogiek, Yiaku and Sengwer Indigenous Peoples to document their biophysical and cultural landscapes. The objectives of these community-led interventions included enhancing inter-generational information exchange, adding value and authority to local knowledge, improving communication with mainstream society, improving planning on sustainable management of natural resources and addressing territorial disputes.

In Kenya P3DM been used by Ogiek, Yiaku and Sengwer Indigenous Peoples to document their biophysical and cultural landscapes. The objectives of these community-led interventions included enhancing inter-generational information exchange, adding value and authority to local knowledge, improving communication with mainstream society, improving planning on sustainable management of natural resources and addressing territorial disputes.  The Indigenous Peoples of Africa Coordinating Committee (IPACC), a pan-African network of 150 organisations adopted the method and is spearheading its adoption in the African Continent to improve awareness at policy-making level on the relevance of location-specific traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in climate change adaptation and mitigation processes. Read more.

The Indigenous Peoples of Africa Coordinating Committee (IPACC), a pan-African network of 150 organisations adopted the method and is spearheading its adoption in the African Continent to improve awareness at policy-making level on the relevance of location-specific traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in climate change adaptation and mitigation processes. Read more.UNESCO has been supporting the adoption of P3DM in Niger and Kenya in the context of the of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage paying specific attention on the opportunity for safeguarding traditional ecological knowledge as part of overall intangible cultural heritage and its integration into the education curricula.

In collaboration with national and regional partner organisations, the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation EU-ACP (CTA) is supporting the dissemination and adoption of P3DM practice in ACP countries. Regional capacity building exercises are scheduled in Central Africa (Gabon and DCR), West Africa (Niger) and Southern Africa (Botswana) in 2010 and 2011.

In collaboration with a number of development agencies, CTA is spearheading the production of a training kit supporting the spread of good practice in generating, managing, analysing and communicating spatial information. The kit includes a module on participatory 3D Modelling.

Other initiatives include the ongoing online participatory translation of a video documentary on P3DM “Giving the Voice to the Unspoken” using the free platform http://dotsub.com/

Thursday, June 11, 2009

Sculpture and Science help in Planning to Preserve The Mutton Hole Wetlands in Australia

A 3D model of the Mutton Hole Wetlands near Normanton has been developed as a starting point for community consultation and discussion about how best to preserve and use the Mutton Hole Wetlands.

A 3D model of the Mutton Hole Wetlands near Normanton has been developed as a starting point for community consultation and discussion about how best to preserve and use the Mutton Hole Wetlands.The Mutton Hole Wetlands are situated just to the North and West of Normanton, and are a part of the Southern Gulf Aggregation, the largest continuous wetland of its type in northern Australia. Being vital for bird migration routes across northern Australia, the Southern Gulf Aggregation is considered to be of state, national and international significance.

In the past the wetlands formed part of the neighbouring Mutton Hole cattle station, but the area was declared a Conservation Park in 2004. Currently managed by Queensland Parks and Wildlife, Carpentaria Shire Council has been considering managing the park themselves. As a part of this consideration the Northern Gulf Resource Management Group has gained funding to write a management plan for the wetland.

The management plan will highlight Aboriginal culture as well as the environmental values of the wetland in a plan to conserve it for future generations. There is strong support from the scientific and local community for use of the wetlands for bird watching, teaching and eco-tourism. As a step towards greater community consultation a model of the wetland area was built and is now located in the Normanton Visitor Information Centre (Burns Philp Building).

The management plan will highlight Aboriginal culture as well as the environmental values of the wetland in a plan to conserve it for future generations. There is strong support from the scientific and local community for use of the wetlands for bird watching, teaching and eco-tourism. As a step towards greater community consultation a model of the wetland area was built and is now located in the Normanton Visitor Information Centre (Burns Philp Building).Over six weeks in April and May 2009 students and staff from Normanton State School and the Gulf Christian College worked together with Dr Isla Grundy of CSIRO to construct a 3D model of the Mutton Hole Wetlands, using a technique called Participatory 3D Modelling (P3DM).

The model was made by first tracing the image of the wetlands from a 1:9500 satellite image onto a large piece of cardboard, then other features were added on or cut out. Finally, the rest of the landscape was painted onto the cardboard and the boundary of the Conservation Park marked with thread.

P3DM is a relatively new technique developed in the Philippines to support collaborative resource use and management, aimed to facilitate community participation in problem analysis and decision-making. This is the first time this participatory technique has been used to make a landscape model from cardboard in Australia.

Since mid-May 2009 the model has been displayed at the Normanton Visitors Information Centre and on Thursday 21st May there was a formal public opening when students, parents and interested community members came to see what the schools had been working on. The exhibition was opened by Vicki Jones of Northern Gulf, along with Isla Grundy of CSIRO and Agnes Hughes from Normanton State School. The forty or so people who attended were able to take a closer look at the model and discuss wetland history and potential use. The community at large was invited to give it’s opinions and ideas on how the Mutton Hole Wetlands should be managed and used in the future through individual community consultations and group discussions held at the Information Centre.

Since mid-May 2009 the model has been displayed at the Normanton Visitors Information Centre and on Thursday 21st May there was a formal public opening when students, parents and interested community members came to see what the schools had been working on. The exhibition was opened by Vicki Jones of Northern Gulf, along with Isla Grundy of CSIRO and Agnes Hughes from Normanton State School. The forty or so people who attended were able to take a closer look at the model and discuss wetland history and potential use. The community at large was invited to give it’s opinions and ideas on how the Mutton Hole Wetlands should be managed and used in the future through individual community consultations and group discussions held at the Information Centre.Community Agro-Ecologist CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems,

JCU / CSIRO Tropical Landscapes Joint Venture

Australian Tropical Forest Institute, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD 4870

Saturday, May 09, 2009

Interview with Mr. Million Belay, coordinator and facilitator of the P3DM exercise recently conducted in Bale, Ethiopia

My name is Million Belay. I am Ethiopian. I am a graduate in Tourism and Conservation, currently doing PhD on bio-cultural diversity. I am the director of MELCA Ethiopia.

Q2: In 2006 you attended a training on Participatory 3D Modelling (P3DM) organised by CTA in collaboration with ERMIS-Africa in Nessuit, Kenya. At that time what were your thoughts about the P3DM method?

I was not sure about it. It did not strike me as something special. But after seeing how it has mobilized the knowledge of the local community, I was really impressed. I have some experiences in community mapping but P3DM was beyond my expectations. I still feel as if I know the Mau complex even if I did not visit it physically.

Q3: Did you think about replicating the P3DM process in Ethiopia?

Yes very much. That was what was in my mind since I came from Kenya. I had to wait for the right time though.

Q4: How did you go about organising the exercise in Bale?

The P3DM handbook (Participatory 3D Modelling: Guiding Principles and Applications) was extremely useful. The website www.iapad.org was also an excellent source of complementary information. I could get almost all of the answers from the handbook. My communication with Giacomo Rambaldi from CTA was a huge help. Our face to face discussion in at the IUCN World Congress in Barcelona also helped a lot, although one has to live through the experience to really understand it. I had to use substitutions for the materials suggested in the guide. I had to encounter a difficulty to understand what some of the recommended inputs were meant to serve for. Every bit was a challenge and meeting those challenges was an exhilarating experience.

Q5: You have now undergone a P3DM process in the role of lead facilitator. What are your most important considerations in terms of participation of knowledge holders in the process?

I think that P3DM is an excellent tool for community participation. The first group of participants was challenged. We had about seven groups. We prepared the map legend before the model has started. After it was assembled, we invited the first community and asked them for a feedback. They changed some legend items. There was a heated argument about the location of some of the rivers. We had forgotten to put one mountain on the Model and that has resulted in some confusion. One mountain was incorrectly named on the source map and this generated a lot of discussion. But local knowledge holders corrected the name. Later on a cartographer confirmed that the source map was incorrect. The women were very strong. They would not accept what the men were suggesting. The men had to reconcile. There was no bystander. The youth and children also participated in the discussions. They were suggesting the names of some of the places and checking these with the elders. It was a fascinating exercise. Local Government officials participated as well. The mayor of the small town said, for example, that if we need to construct a house to place the model, he will give us land. So I found the model to be a social catalyst.

Q6: Did you collect feedback from participants? If yes, which one were the most revealing statements?

Yes! Most of the participants stated that the model revealed them a broader landscape. There were many sad comments also.

One elder stated that “You see I know that the area where I live is degrading. Forests are disappearing. I used to tell myself that ... well, it is only here. The other part of Bale is fine ... But after I saw the model, I could see that Bale in general is degrading. Forests are disappearing. Agriculture is expanding. Grazing areas are disappearing. I really feel very sad and alarmed.

A woman said “Well, as a woman I am not expected to go far. I only know some water points and areas where I collect fire wood. I also know villages of my relatives. Now I can see a larger landscape. Through the discussion I now understand what the Bale Mountains look like. This has broadened my understanding of what we have and what our problems are.”

An elder stated “You know we used to have big forests that we protect through out beliefs. Nobody touches these forests. Now I hear that this practice is rapidly declining. We are loosing our forests because of this. This generation does not understand the value of these things. They ridicule it. I can see that Bale is becoming naked. It is as shameful as undressing a women in public.”

Q7: How would you describe women’s participation compared to the one you observed in Nessuit, Kenya?

They did not wait till the men went for lunch, like it happened in Kenya. They were fighting every bit for their voice to be heard. We have asked deliberately for women to be included among participants. They were so proud that they were invited. They also had more specific knowledge about some areas including rituals related to crossing points on a river.

I was amazed by their active participation as Bale is mainly Muslim and women are usually marginalized.

Q8: Who is going to safeguard and update the 3D model which is now hosted at the Dinsho School?

The model was officially handed over to the school. So presently the school will be the guard. But there is a discussion among MELCA and the other government officials that we should construct a house for it and host it in a larger and protected space. MELCA has a soil and water conservation as well as environmental education program in Bale. So we will use the model for this purpose. We are going to organize a three-day planning workshop on how best to use the model. The event will help us on how to best to use the model and how to continuously update it.

Q9: Are there any plans for extracting and digitizing the data visualised on the model? If so, what will be the role of the community in the process and in the management of the resulting data sets?

Yes there will be digitizing the data. There will be discussion with the community which layers they want to show and which to maintain confidential. We will also handover the printed maps to whomever they chose. We will also have a discussion with them on where to store the data. We have explained to them the purpose of the model and they have agree to participate in the process and are so glad that it was done.

Q10: Do you plan to facilitate the replication of the P3DM process elsewhere in Ethiopia?

Yes. We will do two models in Ethiopia probably in June and July 2009. We will see how it goes and will replicate it in other locations as well. What is so exciting is that our partners in the other parts of the Bale Mountains are planning to adopt the P3DM process as well. It is self replicating, it seems.

Monday, May 04, 2009

Participatory 3D Modelling in Bale, Ethiopia

The exercise has been done to assist local communities in planning out a more sustainable management of the area, reviving local bio-cultural diversity and supporting local environmental education.

More information on the exercise is found here.

Tuesday, April 07, 2009

PPgis.Net members on LinkedIn

ICT4D: Information and Communication Technology for Development

It combines theory with practical guidance – including both a conceptual framework for understanding the rapid development of ICT4D, and practitioners’ overviews of the use of ICTs in enterprise, health, governance, education and rural development.

Boxed case studies provide detailed examples of issues and initiatives from a wide variety of countries and organisations.

Wednesday, March 18, 2009

Learning and Knowing in Indigenous Societies Today, UNESCO Report

Edited by P. Bates, M. Chiba, S. Kube & D. Nakashima, 2009

The loss of their specialised knowledge of nature is a grave concern for many indigenous communities throughout the world. Changes to the social environment, generally brought on by the introduction of new technologies, lifestyles and market economies through colonisation and modernisation, undermine the transmission of ‘indigenous’ or ‘traditional’ knowledge. This process is often accompanied by the transformation of the natural milieu, for example when rainforests are converted to pasturelands, or valleys are flooded to become reservoirs, radically altering the arenas in which indigenous knowledge would be acquired and passed on.

The issue of education, as it is understood in a Western context, occupies a pivotal role in this process, highlighted by many as both a major cause of the decline of indigenous knowledge, and also as a potential remedy to its demise. In the classical Western understanding of the term, education tends to involve learning through instruction and reading, and by internalising abstract information which may later be applied in specific real-world contexts. For many indigenous cultures, however, learning occurs through the process of observing and doing, and by interacting over long periods of time with knowledgeable elders and the natural environment. This learning process is so subtle and unobtrusive that often it is not recognised as learning at all, even by the learners themselves. The knowledge resulting from this latter process is not necessarily abstract information, but is instead intricately bound to experiential process. For many indigenous peoples, knowledge is thus an integral aspect of a person’s being, and by separating it from its context one may render it meaningless.

As might be imagined from these fundamentally contrasting epistemologies, it seems that the two ways of learning – Western and indigenous – may be uncomfortable bedfellows. Time spent by indigenous children in classroom settings is time that they are not spending learning through experience on the land, weakening their knowledge of the local environment and their interactions with the community. In formal schooling, teachers are figures of authority and Western ‘scientific’ knowledge is often presented as the ‘superior’ way to understand the world. This weakens the respect that children have for community elders and their expertise. Furthermore, curricula may contain little of relevance to local realities or may actively denigrate local culture.

Colonial languages are frequently the modes of instruction, further hastening the decline of indigenous and vernacular languages, and widening the rift between elders and youth. Many indigenous communities are therefore in a quandary. While formal education promises to open pathways to the material benefits of the Western world, at the same time it tends to be destructive to indigenous knowledge and worldviews. Furthermore, education curricula, designed for a mainstream and largely urban populace, may be of limited utility for remote rural communities where wage-earning jobs are few and far between. Indeed, acquiring indigenous knowledge of how to navigate and survive on the land, and how to use local resources to feed, clothe and provide for one’s family, may be of much greater relevance for the contexts in which many indigenous groups continue to live today.

Commendable efforts are being made to better align educational curricula with indigenous realities by incorporating local knowledge and language content, but the interrelationship and balance between the knowledge forms remains delicate. These issues, and attempts to address them, are explored within this volume.

Thursday, March 12, 2009

Written In the Land, the Life of Queenie McKenzie

The story is told often in Queenie’s own words and shows the many ways that indigenous people are connected to the land, it discusses issues such as mining of sacred sites, dreaming sites, skin groups - the Australian indigenous governance system, rainbow snake, massacres and parts of the history of growing up as an indigenous child during the impacts of white settlement. As Queenie was an acclaimed artist it also contains many images of her artwork, her maps of her country and sacred sites.When Queenie passed away these traditional ‘law’ practices ceased. Many years before Queenie had revived these annual practices after they were stopped during the settlement time, it was in the 1980’s that she insisted that they begin again. It has been 10 years since her death and the work on the book began between the author and the female elders, to keep Queenie’s legacy strong. Funds from the book are returned to the community for that purpose. It is a tragic reality that Queenie’s generation are the last remaining elders of the area who hold the land based knowledge of sacred sites, these people will all be gone within 2 years yet this is not seen as an urgent need in Australia by the Government, to provide resources and training to indigenous people to map these sacred locations and the associated knowledge.

The story is told often in Queenie’s own words and shows the many ways that indigenous people are connected to the land, it discusses issues such as mining of sacred sites, dreaming sites, skin groups - the Australian indigenous governance system, rainbow snake, massacres and parts of the history of growing up as an indigenous child during the impacts of white settlement. As Queenie was an acclaimed artist it also contains many images of her artwork, her maps of her country and sacred sites.When Queenie passed away these traditional ‘law’ practices ceased. Many years before Queenie had revived these annual practices after they were stopped during the settlement time, it was in the 1980’s that she insisted that they begin again. It has been 10 years since her death and the work on the book began between the author and the female elders, to keep Queenie’s legacy strong. Funds from the book are returned to the community for that purpose. It is a tragic reality that Queenie’s generation are the last remaining elders of the area who hold the land based knowledge of sacred sites, these people will all be gone within 2 years yet this is not seen as an urgent need in Australia by the Government, to provide resources and training to indigenous people to map these sacred locations and the associated knowledge.For more information about the book go to http://www.writtenintheland.com/ or http://www.culturalmapping.com/

Sunday, January 18, 2009

Geotagging Picasa photos in Google Earth

Funding opportunities for NGOs, CBOs and researchers

Wednesday, January 14, 2009

2009 PGIS / PPGIS Photo Competition launched by CTA

The competition has been launched to enrich the library with a wide variety of examples and applications from around the world. The competition allows development practitioners and researchers to share photographic records of their experiences with other peers and contribute to a product (the training kit) which will be freely available in different languages in 2010. More about the competition, its legal conditions, guidelines for submission and procedures of selection and awarding is found on the recently launched CTA web site dedicated to Participatory GIS (PGIS) practice.